ABOUT

The Tervuursepoort (Tervuren Gate) used to be one of the 14th-century outer city defence gates of Leuven. It is now part of the city’s ring road, that links the intra-muros Tervuursestraat to the extra-muros Tervuursesteenweg. Unbeknownst to many nowadays, Tervuursepoort was one of the Seven Wonders of Leuven and its most beautiful and mighty city gate.

Origin

1355-60: Leuven bulks up its defence walls

By the middle of the 14th century, Leuven began to lose its political and economic status as the capital of Brabant. Both Brussels and Antwerp began to grow richer and more powerful. Poverty began to spread throughout the city, with less and less income from its weaving trade (see Lakenhalle) and wine production (see Wijnberg). After the Brabant Succession War in 1355, Leuven dug deep into its pockets to build the 7km-long outer (second) city walls, which were completed in 1360. With its eight new modern city gates, Leuven could essentially shut itself off from invaders (starting from the north in clockwise, with modern names in brackets):

Aarschotse poort (Vaartpoort)

Dorpstrate Buiten-Poort (Diestsepoort)

Hoelstrate Buiten-Poort (Tiensepoort)

Parkpoort

Heverse Poort (Naamsepoort)

Groefpoort (Tervuursepoort)

Wyngaerdenpoort (Brusselsepoort)

Buiten-Borch poort (Mechelsepoort)

The walls also came with 48 watch towers. The later-built and very imposing Verloren Kosttoren (Tower of Lost Cost) would be incorporated into this outer wall system as its 49th and tallest watch tower.

The new outer city walls now protect and include parishes like Sint-Kwintens and Sint-Jacobs which were previously outside the first city walls against attacks launched by the Count of Flanders, Lodewijk van Male. The new walls would also have increased the city area to nearly seven times. The outer city walls were completely surrounded by a moat measuring 3-4m deep and 10-15m wide, depending on the terrain. Where the moat was not dry, it was filled with water. This occurred twice: in the south where the Dijle and the Voer flowed into the city, and in the north where the Dijle and the Vunt flowed out of the city.

The destruction of Leuven’s city walls

In 1781, Habsburg Emperor Jozef II decreed the dismantling of all city defenses, except Antwerp. Cities were only allowed to keep the embankments and canals to avoid the fines. Somehow, Leuven managed to only demolish the defense structures built in 1672 and 1674. The rest of the city fortifications were preserved. But with the French occupation that followed, the outer city walls were completely dismantled, while the city gates were partially or fully demolished. All this was replaced by parks and promenades (any of the roads along the ring ending with the word ‘-vest’ indicates this development).

Between 1950 and 1980, many of the parks and promenades gave way to roads, and with the expansion of the ring around Leuven in 1970, whatever remained of the outer city walls fully disappeared.

What's so special about this place?

The City Gate of Many Names

With the exception of Parkpoort, all the outer city gates of Leuven did not keep their original names from the 14th century. But the Tervuursepoort seemed to be called by more appellations than one could count. And with good reasons.

1. Groefpoort

When the Tervuursepoort was first built in 1358, it was called the Groefpoort. This was because the intra-muros street that led to it was known as the Groefstraat, today it is the Tervuursestraat. First recorded in the end of 13th century, Groefstraat was named after the stone furrows called ‘steengroeven‘ (cognate with the English ‘groove‘) located just outside the city gate all the way to Terbank. Groefstraat was a small narrow street – it still is today – that led from the Blauwe Hoek on the Brusselsestraat to the city gate.

2. Bankpoort

But the Groefstraat was also called the Bankpoort. This was because the city gate led directly to the Priorij Terbank (Priory of Terbank) located just 1km outside the city.

Founded in 1197 by the Prince-Bishop of Liege, Hugo de Pierrepont, and the Bishop of Palestrina, Guy de Nuntius, the priory was run by Augustinian sisters who cared for Leuven’s sick and dying. A century later, the priory ran a successful leprosy colony, that served not only Leuven but the whole of the Duchy of Brabant.

3. Kasteelpoort/ Poort naar Ter Bourg

There was a third name of the Tervuursepoort: Kasteelpoort (Castle Gate). This was because when one reached the Priory at Terbank, turning south would put you on the road to the Kasteel van Arenberg (Arenberg Castle).

The Most Renovated City Gate

This brings us to the next interesting point about the Tervuursepoort, that it was the most renovated outer city gate of Leuven and also because of its fourth name.

4. Brusselsepoort

By the time the city gate was built, the Duke of Brabant had started spending more time in Brussels rather than in the capital Leuven. As a result, the Tervuursepoort that not only led to Terbank, but also westwards to Brussels was a dull reminder to the Duke of how the capital was less attractive. In 1384, a more impressive city gate was put in its place under the supervision of Hendrik van Sammen, drawn by architect Jan van Hove.

Still, the Duke preferred Brussels.

And in the 15th century, Leuven went on an overdrive to get the political support back. The university was established in 1425. As a response to Brussels’ new city hall in 1401, Leuven built its even more impressive one from 1439 to 1469, in addition to a Tafelrond. On top of that, the main city square was moved from Oude Markt to in front of the brand new city hall on the Grote Markt.

To welcome the Duke whenever he returned for a visit, the Tervuursepoort aka Brusselsepoort was torn down and completed renovated in 1426. The work, supervised by Sulpice van Vorst, was done in record speed from 20 April to October the same year.

The Terror Attack by Maarten van Rossum in 1542

Lord Maarten van Rossum (Zaltbommel, 1490 – Antwerpen, 7 June 1555) was the terrorist of the 16th century. He was the military commander of the Duke of Guelders (Geire) Karel. Born of Guelder noble descent, his family coat of arms featured three red birds on a silver shield and the motto was ‘Terror Terroris‘.

Living up to his family motto, he led the Gelders army to plunder and kill throughout the Low Countries for ransom and to satisfy his thirst for bloodshed. His aim was also to ensure the Duchy of Guelders together with the Bishopdom of Utrecht were not under the total control of the Holy Roman Empire like Brabant and Holland.

Maarten van Rossum’s name was synonymous with terror, as civilians suffered more than normal when he and his army attacked any Habsburg city.

On 15 July 1542, van Rossum declared war on Brabant. The moment he set foot on Brabantine territory, he set everything he saw on fire. His plan was to cross the River Maas, make his way to Leuven before setting further west. So when he reached Leuven, he actually did not manage to capture it.

Thanks for the constantly renovated and thus fortified Tervuursepoort, this city gate where van Rossum launched his attack held him off, despite suffering severe damages.

In an old songbook from 1543, “Antwerpsche Liederboek van 1543”, a song was written about van Rossum’s ‘failed’ attack on Leuven on 2 August 1542:

“XXXVIII. Lied op Maarten van Rossums mislukten Aanslag op Leuven.”

Een nyeu Liedeken.

1.

In Augusto den tweesten dach,

Datmen de stadt van Loven belegen sach

Al van de Fransche knechten,

Daer Merten van Rossum sonder verdrach

Die Luevenaers woude bevechten.

2.

Die Fransoysen quamen seer stoutelic aen,

Si meynden te Lueven binnen ghaen,

Ghelijck een scheper drijft sijn schapen;

Sonder slach oft sonder slaen

Meynden de Lovensce vroukens beslapen.

3

Op de veste was menigen stouten clerc,

Die vroukens waren neerstich int werck,

Aen steenen, aen reepen, aen alle dinghen.

Si spraken: ‘Sijt alle cloec int werck,

Wi sullen u ghenoech aen brenghen.’

4

De Fransoysen schoten hen bussen af,

Die van Loven en achten dat niet een caf,

Die burghers hielden goe hoede.

Al waert dat hen veel volcx beghaf,

De schutters waren cloec van moede.

5

Merten van Rossum, den onverlaet,

Hi heeft ghesonden eenen abasaet

belegen, belegerd.

Al aen die burghers ghetrouwe:

Hi eyste met woorden seer obstinaet

Tseventichduysent cronen, root van gouwe.

6

Daer boven eyste hi noch een voor al

Van clooten, van bussen, een groot ghetal,

En poeyer met gheheelder ermijen,

En dat hi ses weken sonder gheschal

Wt ende in sou moghen rijen.

7

Die heeren hebben verstaen dit woort,

Die borghers waren seer verstoort:

Si enwouden dat niet consenteeren,

Si spraken altsamen met een accoort:

‘Wi willense declineren.’

8

Merten van Rossum hen capiteyn,

Hi hielt voor de stadt van Loven ghemeyn;

Dat heeft den borghers verdroten.

Si riepen: ‘Comt aen, groot ende cleyn!’

En si hebben inden hoop gheschooten.

9

Die Fransoysen waren seer vervaert,

Doort schieten is hen den moet beswaert,

Achter rugghe sijn si ghetoghen.

Dus danct God, d[i]e zyn dienaers heeft bewaert,

Want het staet doch al in sijn vermoghen.

10

Merten van Rossum was in grooter noot,

Want daer bleeffer meer dan iiij.c. doot;

Dies was hi ghestoort van sinne,

Mer in een groote schure, verstaget bloot,

Daer dede hise varen inne.

11

Die Fransoysen waren seer vervaert,

Si hebben al tsamen verbaert:

Die dooden metter schueren,

Die stadt van Loven was hen ontvert,

Dat mochten si wel betrueren.

12

Als God zijn dienaers helpen wilt,

Tegen hem en helpet tswaert noch schilt,

Dan alleen in die hant des Heeren.

Dus laet ons tot God keeren als ridder milt,

Hi sal hem tonswaert keeren.

13

Die dit liedeken heeft ghedicht,

Sijn hert dat was daer toe verlicht,

Om elcken te vermonden;

Want ghelijck een leeu d[i]e cloeckelijck vicht,

Sijn die van Lueven bevonden.

While the Maarten the Terrorist did not manage to destroy Leuven, its surrounding countryside, as in the case of Antwerp where he also attacked, was completely flattened. As a result, for a century that followed, the countryside of these two Brabant cities were more rural than two centuries before.

5. Oude Brusselsepoort

With the construction of another route to Brussels departing from the Wijngaert Poort, which was renamed the new ‘Brusselsepoort‘. The Tervuursepoort was awkwardly named the ‘Oude Brusselsepoort‘. No wonder a new route was plotted to link up Leuven and Brussels, as I can imagine it not being very pleasant for the successive generations of Brabant Dukes and citizens alike to pass by the leprosy colony all the time.

The destruction brought about by the terror attack of Maarten van Rossum made it imperative to renovate yet again the Oude Brusselsepoort. On 19 September 1567, the city magistrate ordered the reconstruction of the Oude Brusselsepoort into something even bigger and grander.

The even newer, stronger Tervuursepoort was thus born.

The Siege of Leuven in 1635

The Dutch Revolt was never really about religion. As we all know (hopefully), religion is but a political weapon to summon the masses.

The Siege of Leuven that took place from 24 June to 4 July in 1635, is known as the ‘Beleg van Leuven‘. During this time, the Sint-Pieterskerk remained open day and night, so that citizens could burn offerings to Mother Mary. The siege itself was composed of French and Dutch (at that time, the latter were known as ‘Protestants’) soldiers which tried to enter Leuven by water on the River Dijle via the Grote Spui. Habsburg troops based in Leuven prevented the entry.

The attackers then moved west to the Tervuursepoort and tried digging under it.

But the frequently renovated city gate was just too massive to fall to their digging. On top of that, the roots of the trees that topped the gate actually went deep into the ground (see below about the Seven Wonders of Leuven). So that didn’t work.

They then focused their attack on the next gate, the Mechelsepoort outside the Keizersberg, thinking that the ravelin at the Mechelsepoort was a weak spot. But by the time they arrived at the gate on 27 June, they were beaten off by ferocious Leuven women who were fighting alongside Habsburg soldiers and university students.

After being ravaged by ferocious Leuven women, the Franco-Dutch attackers were ambushed on the night of 29 June 1635 by Habsburg troops who stormed out of the Tervuursepoort, the Brusselsepoort and the Mechelsepoort, and the ambush was coordinated from Leuven’s tallest defense structure, the Verloren Kosttoren.

When the Holy Roman army from Namur arrived five days later at Leuven, the Franco-Dutch troops fled, thus ending the Siege of Leuven.

In the 1639 painting called the ‘Relief of Leuven’ by Peter Snayers, you can visualise the great defense capacity of Leuven in the 17th century with its outer city gates.

One of the Seven Wonders of Leuven

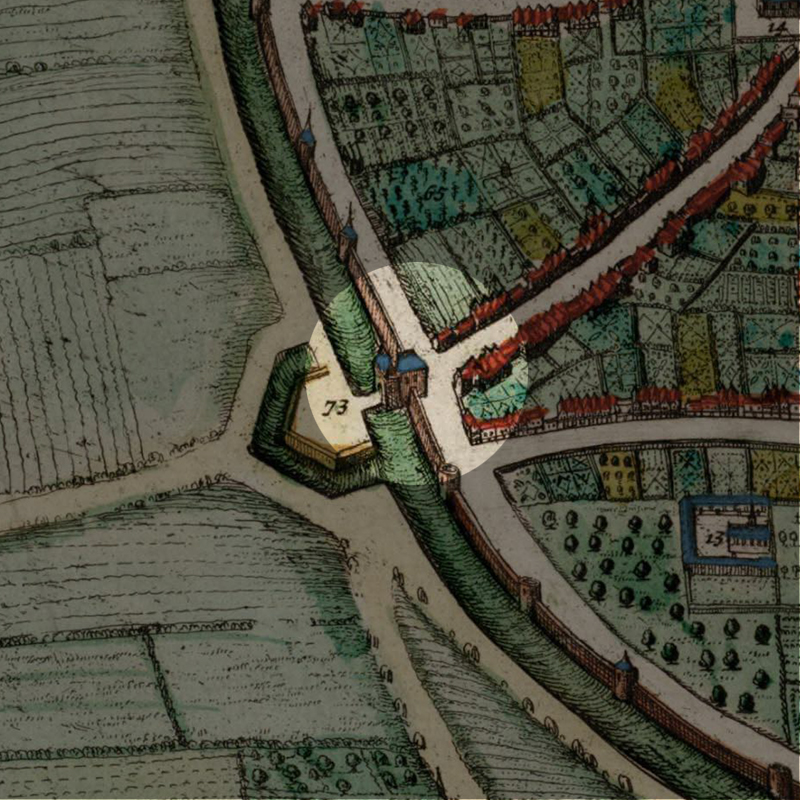

The Tervuursepoort was one of the famous Seven Wonders of Leuven. On the extra-muros side, the gate was guarded by a triangular ravelin and a deep moat.

After crossing into the first gate, one went through a grand arched arcade with two towering bastions, both topped with sharp tiled roof. Between the arcade and the city-side building was a courtyard. When one looked up in the courtyard, the city-side arcade was an even taller building with elms growing on the roof. One had to walk under the elm-covered roof to enter the city. The thick roots of the trees penetrated the walls reaching into the grounds below, thus the Tervuursepoort became known as one of the Seven Wonders of Leuven:

“Mensen lopen onder Boomwortels”

Men walk under Tree Roots

Unfortunately, after the French Occupation in 1789, Leuven started to lose its city gates. The Tervuursepoort was demolised in part in 1807, in 1829, and then completely in 1886.

In the 19th century, there was even a tramline that led directly to Tervuren right from the former spot of the Tervuursepoort.

Current situation

Today, the Tervuursepoort is as unremarkable as a traffic junction can be. It is hard to imagine this used to defend Leuven from formidable attackers, twice in fact. And it was even one of the Seven Wonders. The next time you pass by the Tervuursepoort, imagine yourself walking through its massive stone arcade and under the roots of the towering elms.

Sources:

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geschiedenis_van_Leuven

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringmuren_van_Leuven

“Louvain dans le passé et dans le présent’, Edward van Even, 1895 (Image)

Many thanks to: Marc Mellaerts, Stadspoorten van Leuven (Pinterest)

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/themas/8260

https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/graf001midd01_01/graf001midd01_01_0040.php

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beleg_van_Leuven

Many thanks to: Leuven Weleer (leuven.weleer.be) for the use of the photos

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.