ABOUT

The Tiensepoort (Tienen Gate), once an imposing city gate of the city of Leuven, does not exist anymore. Today, it is a busy junction on the ring road of the city, where the intra-muros Tiensestraat leads to the extra-muros Tiensesteenweg.

Origin

1355-60: Leuven bulks up its defence walls

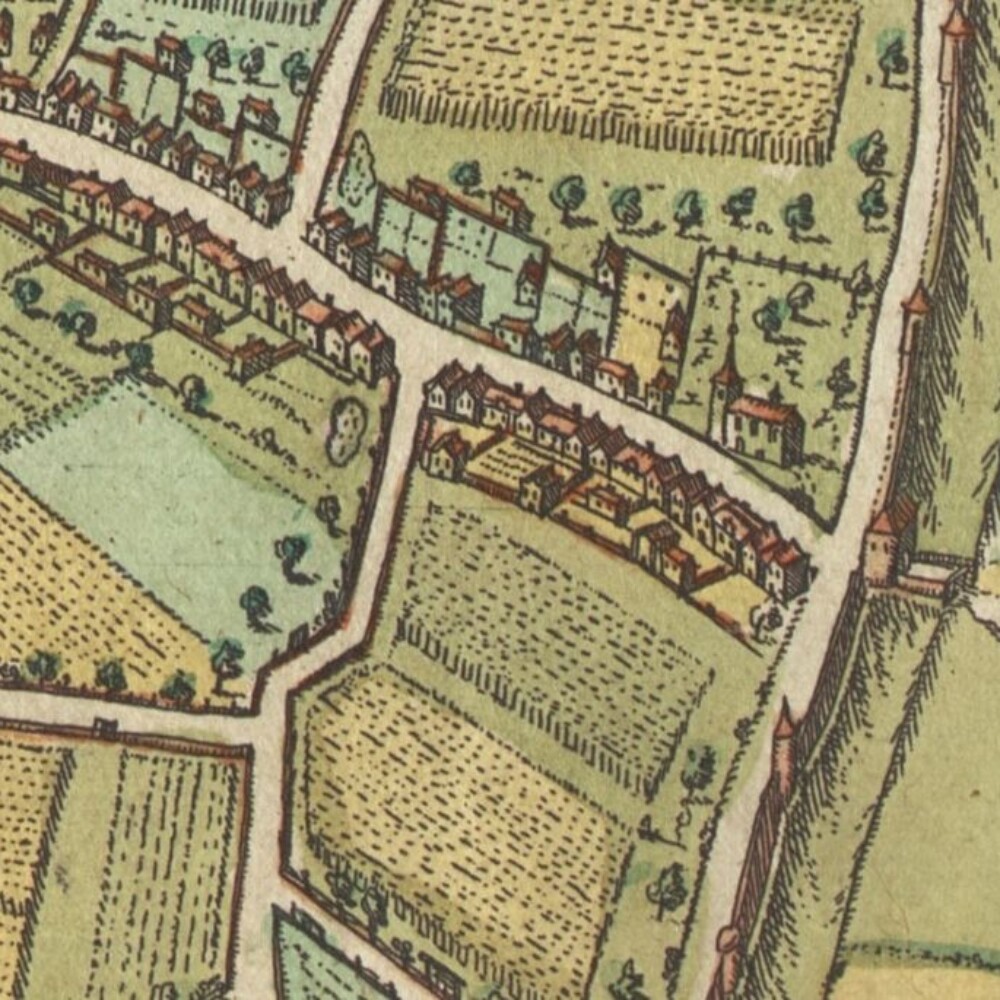

By the middle of the 14th century, Leuven began to lose its political and economic status as the capital of Brabant. Both Brussels and Antwerp began to grow richer and more powerful. Poverty began to spread throughout the city, with less and less income from its weaving trade (see Lakenhalle) and wine production (see Wijnberg). After the Brabant Succession War in 1355, Leuven dug deep into its pockets to build the 7km-long outer (second) city walls, which were completed in 1360. With its eight new modern city gates, Leuven could essentially shut itself off from invaders (starting from the north in clockwise, with modern names in brackets):

Aarschotse poort (Vaartpoort)

Dorpstrate Buiten-Poort (Diestsepoort)

Hoelstrate Buiten-Poort (Tiensepoort)

Parkpoort

Heverse Poort (Naamsepoort)

Groefpoort (Tervuursepoort)

Wyngaerdenpoort (Brusselsepoort)

Buiten-Borch poort (Mechelsepoort)

The walls also came with 48 watch towers. The later-built and very imposing Verloren Kosttoren (Tower of Lost Cost) would be incorporated into this outer wall system as its 49th and tallest watch tower.

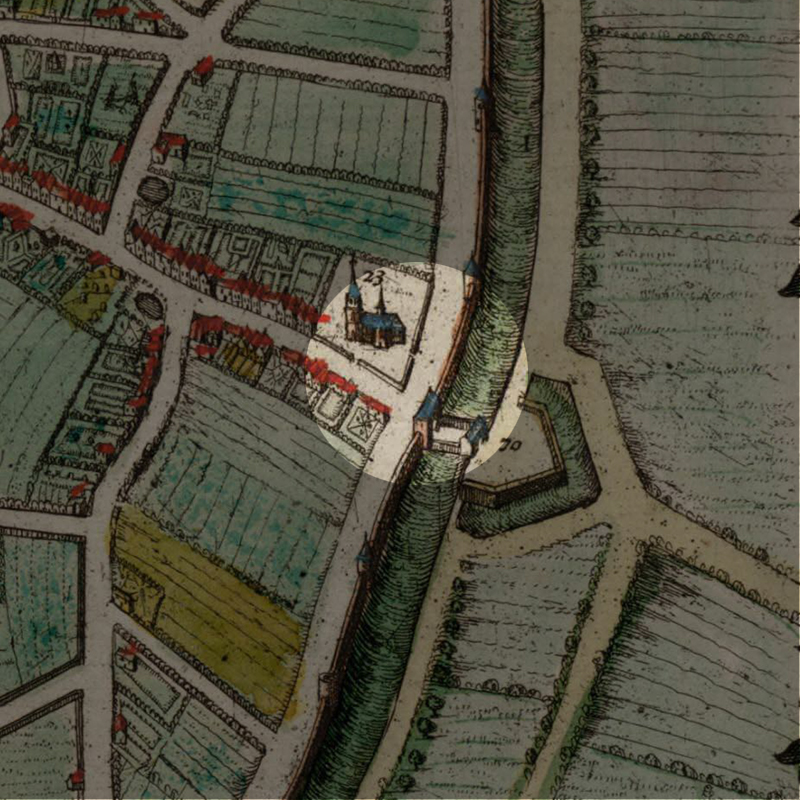

The new outer city walls now protect and include parishes like Sint-Kwintens and Sint-Jacobs which were previously outside the first city walls against attacks launched by the Count of Flanders, Lodewijk van Male. The new walls would also have increased the city area to nearly seven times. The outer city walls were completely surrounded by a moat measuring 3-4m deep and 10-15m wide, depending on the terrain. Where the moat was not dry, it was filled with water. This occurred twice: in the south where the Dijle and the Voer flowed into the city, and in the north where the Dijle and the Vunt flowed out of the city.

The destruction of Leuven’s city walls

In 1781, Habsburg Emperor Jozef II decreed the dismantling of all city defenses, except Antwerp. Cities were only allowed to keep the embankments and canals to avoid the fines. Somehow, Leuven managed to only demolish the defense structures built in 1672 and 1674. The rest of the city fortifications were preserved. But with the French occupation that followed, the outer city walls were completely dismantled, while the city gates were partially or fully demolished. All this was replaced by parks and promenades (any of the roads along the ring ending with the word ‘-vest’ indicates this development).

Between 1950 and 1980, many of the parks and promenades gave way to roads, and with the expansion of the ring around Leuven in 1970, whatever remained of the outer city walls fully disappeared.

What's so special about this place?

Hoelstrate-Buiten-Poorte, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe-Poorte

Before the 17th century, the road leading to the new and outer city gate of 15th century Tiensepoort from the first and old 12th century city gate of Sint-Michielspoort was known as the ‘Hoelstrate‘. When this new gate was built, it was simply called the ‘Hoelstrate-Buiten-Poorte‘ (Holestreet Outer Gate).

It was also known as the Onze-Lieve-Vrouwe-Poorte (Gate of Our Lady), after the Kapel van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-ginder-buiten (Chapel of Our Lady Without the Walls) located just ‘inside’ the Tiensepoort. This was because the chapel used to be outside the first city walls.

Since the 17th century, the name ‘Tiensepoort‘ was used, together with the change in the name of Hoelstrate/Hollestraat to ‘Tiensestraat‘, as the main road outside the gate was called ‘Tiensesteenweg‘ since it led directly to the city of Tienen.

Little is known about the original Tiensepoort, except that it was constructed in 1357 under the supervision of Jan Hooren and Henrik Sammen. The city gate was accessible through a wooden drawbridge and it had a statue of the Holy Virgin in a niche above the entrance.

Whatever the construction was like, by the beginning of the 16th century, it was in a bad shape. The city magistrate decided in 1533 to rebuild the Tiensepoort.

Construction took a long time. From the laying of the foundation in 1534 to the finalisation of the works in 1539, the new Tiensepoort was again not usable 25 years later when the original 14th century wooden draw bridge had to be replaced.

How did the Tiensepoort look like?

After completion, the Tiensepoort was a gigantic massive defence gate that guarded a busy entry point into the city. With the moat outside the gate, it was extremely imposing, and without the ‘new’ wooden draw bridge that was still used in 1779, it was not possible to enter the city.

But as was the case with the other city gates of Leuven, the Tiensepoort was demolished in 1823. In its place, were erected two simple outposts that were similar to those still preserved at today’s Brusselsepoort.

In 1892, the Belgian administration turned a part of the outer city walls (the ‘Vesten’) into a tram way from the train station to Tiensepoort to Naamsepoort). It was first powered by steam and this was later changed to electricity in 1912.

The location of the Tiensepoort itself as you can see in the photos, was turned into a roundabout.

Current situation

Today, the Tiensepoort bears no signs of its former massive 16th century city gate. It is just an ordinary-looking, uninspiring traffic junction.

Sources:

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geschiedenis_van_Leuven

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringmuren_van_Leuven

“Louvain dans le passé et dans le présent’, Edward van Even, 1895 (Image)

Many thanks to: Marc Mellaerts, Stadspoorten van Leuven (Pinterest)

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.