ABOUT

The ‘Diestsepoort’ (Diest Gate) is one of the eight city gates inherited from Leuven’s 14th-century outer city fortifications. It is located on the East of the city, at the end of the Diestsestraat.

Origin

1355-60: Leuven bulks up its defence walls

By the middle of the 14th century, Leuven began to lose its political and economic status as the capital of Brabant. Both Brussels and Antwerp began to grow richer and more powerful. Poverty began to spread throughout the city, with less and less income from its weaving trade (see Lakenhalle) and wine production (see Wijnberg). After the Brabant Succession War in 1355, Leuven dug deep into its pockets to build the 7km-long outer (second) city walls, which were completed in 1360. With its eight new modern city gates, Leuven could essentially shut itself off from invaders (starting from the north in clockwise, with modern names in brackets):

Aarschotse poort (Vaartpoort)

Dorpstrate Buiten-Poort (Diestsepoort)

Hoelstrate Buiten-Poort (Tiensepoort)

Parkpoort

Heverse Poort (Naamsepoort)

Groefpoort (Tervuursepoort)

Wyngaerdenpoort (Brusselsepoort)

Buiten-Borch poort (Mechelsepoort)

The walls also came with 48 watch towers. The later-built and very imposing Verloren Kosttoren (Tower of Lost Cost) would be incorporated into this outer wall system as its 49th and tallest watch tower.

The new outer city walls now protect and include parishes like Sint-Kwintens and Sint-Jacobs which were previously outside the first city walls against attacks launched by the Count of Flanders, Lodewijk van Male. The new walls would also have increased the city area to nearly seven times. The outer city walls were completely surrounded by a moat measuring 3-4m deep and 10-15m wide, depending on the terrain. Where the moat was not dry, it was filled with water. This occurred twice: in the south where the Dijle and the Voer flowed into the city, and in the north where the Dijle and the Vunt flowed out of the city.

The destruction of Leuven’s city walls

In 1781, Habsburg Emperor Jozef II decreed the dismantling of all city defenses, except Antwerp. Cities were only allowed to keep the embankments and canals to avoid the fines. Somehow, Leuven managed to only demolish the defense structures built in 1672 and 1674. The rest of the city fortifications were preserved. But with the French occupation that followed, the outer city walls were completely dismantled, while the city gates were partially or fully demolished. All this was replaced by parks and promenades (any of the roads along the ring ending with the word ‘-vest’ indicates this development).

Between 1950 and 1980, many of the parks and promenades gave way to roads, and with the expansion of the ring around Leuven in 1970, whatever remained of the outer city walls fully disappeared.

What's so special about this place?

Dorpstrate Buite-Poorte, Vlierbeekse Poort

Before the street was named Diestsestraat (Diest Street), it was called the Dorpstraat, or Oppendorpstraat, after the village Oppendorp that was located just outside the first city gate located on the same street. When the outer city fortifications were built, the new city gate became known as Dorpstrate Buite-Poorte – The outer gate of the Village Street.

According to historian Edward van Even, the gate was also called the Vlierbeekse Poort, because it led to the Abdij van Vlierbeek (Abbey of Vlierbeek), and the Diestsepoort, because the direct road to Diest laid outside the gate. It was this name that remained with us today.

No one knows how the first Dietsepoort looked like, except that it was built in 1361 and had a draw bridge.

But due to a fire that broke out in the village of Blauweput that spread to the Diestsepoort on 29 April 1518, the original city gate was completely burnt down. It laid in ruins until 1529, when the city magistrate decreed its reconstruction.

How did the Diestsepoort look like?

One of the most majestic buildings of Leuven

The rebuilding of Diestsepoort laid on the shoulders of the old but respected architect Jos Metsys, who designed a huge edifice with two towers on top of a circular foundation. But when the old gate was removed, it was discovered that the ground was too muddy and could be unstable for such a gigantic building. That concern was so allayed when two renowned architects from Brussels and Mechelen arrived in Leuven and gave the green light to proceed.

The stones came from around Leuven, the foundation stones from behind the Abdij van Vlierbeek and the others from Diegem and Gobertange.

After the death of Metsys in 1530, a young man named Walraven took over. When the Dietsepoort was completed a year later, what a sight it was to behold! A sculpture of the Holy Trinity was placed above the giant oak gate on the city side. On the country side, two lions, two griffins and another set of the Holy Trinity adorned the facade.

Two plaques were placed on the monumental Diestsepoort. On the intramuros facade:

VAN DEN BOLLENWERCKE WAS DEN IERSTEN STEEN

GHELYT, BYDER STADT REGEERDERS GHEHERTICH,

IN MEERTE VYFTHIEN HONDERTSESENTWINTICH REEN,

DAER NA DE POORTE, EN VOLMAECKT, AL VIELT SMEERTICH,

IN MEERT, DIAER VYFTIEN HONDERT EENENDERTICH.

On the extramuros side, the plaque wrote:

ALS CAROLUS ROOMS KEYSERE DOMINEERDE,

DOE MEN SCREEF VYFTHIEN HONDERT SESENTWINTICH JAER,

DE STADT VAN LOEVEN DIT WERCK FONDEERDE,

SYNDE TYMPEL, BERICX, BORGEMEESTERS ALDAER.

An ideal prison

The immense size and its seeming impenetrability of the Diestsepoort made it an ideal prison. As early as 1674, one of the cells in the foundation of the Diestsepoort was made, by decree, into a holding cell for ‘women of bad life’.

By 1798, the bridge that led out of the Diestsepoort was in ruins, such as going in and out of the city became a precarious affair. In 1800, the fencing of the edifice was demolished.

But the Diestsepoort survived the fate of the city walls and the other city gates, broken down by the French invaders, because of its sheer monumentality. In 1818, it was given to the government to be converted into a central prison. Renovations started immediately for the conversion, such that by the end of the year, one had to look hard to find traces of the original design of Metsys.

With a much larger prison on the Maria-Theresiastraat, the Diestsepoort had finally finished serving its due. On 5 February 1873, the Diestsepoort – one of Leuven’s monumental city gates – was completely demolished.

Current situation

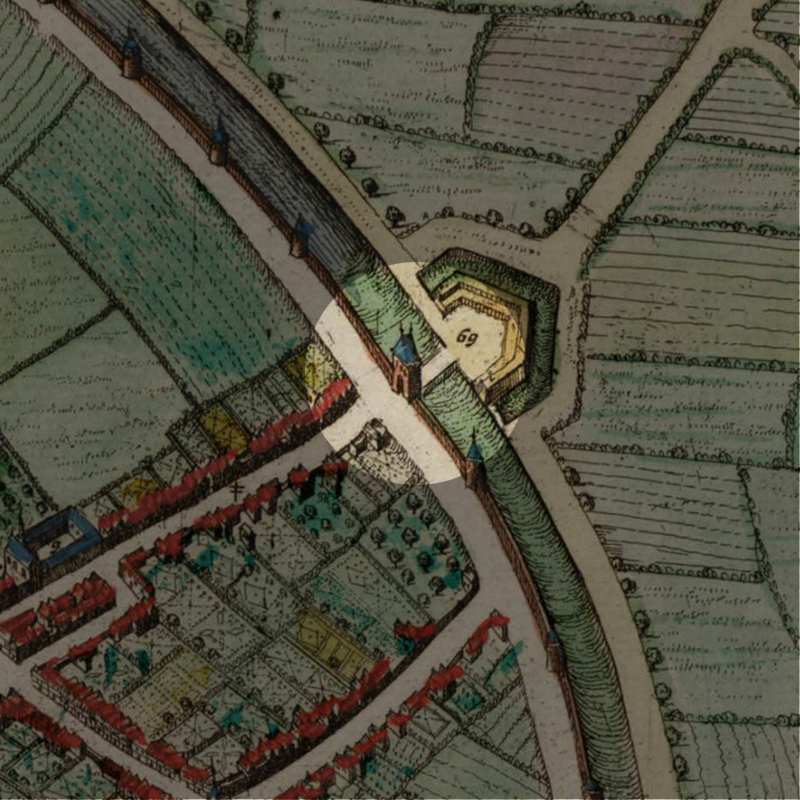

Today, when you reach the end of the Diestsestraat, you arrive at a roundabout, under which a tunnel runs through. Behind the roundabout, is the bus station, itself attached to the train station. Take in this whole scene, because when you look at the surviving sketches of Diestsepoort of the 16th century, you can still recognise the certain elements: the circular gallery is now the roundabout, the mote is now the tunnel, the bus station and the Acerta building were the ramparts and imposing city walls.

Look now again at the old images, note that the bridge that linked to the triangular ravelin outside the Diestsepoort to the road to Diest now called Diestsesteenweg is located on the left of the ravelin. The road behind the Acerta building nowadays called Diestsepoort is exactly the bridge and the beginning of the former Diestsesteenweg.

The Diestsepoort is now one of the busiest spots of Leuven.

Sources:

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geschiedenis_van_Leuven

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringmuren_van_Leuven

“Louvain dans le passé et dans le présent’, Edward van Even, 1895 (Image)

Many thanks to: Marc Mellaerts, Stadspoorten van Leuven (Pinterest)

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.