ABOUT

The Biestpoort (Biest Gate) was located on today’s Brusselsestraat, before where the River Dijle flows. While facing outwards, on its right towards the Minnepoort is the Handbooghof, the best preserved section of Leuven’s first city wall with watch towers dating from the 12th century, on its left towards the Minderbroederspoort is the new development site of Hertogensite where sections of the wall and some watch towers still stand.

Origin

The First and Inner Defence Wall of Leuven: After 1190

In the Early Middle Ages, Leuven was defended by a primitive fence that stretched from the Aardappelmarkt (modern-day Vital Decosterstraat) to the Redingenstraat, while an arm of the River Dijle formed a natural border.

By the 13th century, when the city grew to be the permanent residence of the Count of Leuven and Brussels, the need for a stronger defense bulwark became urgent. Historians have traditionally dated the construction of Leuven’s first defense walls to be between 1156 and 1165, during the reign of Count Godfried III, due to the yearly tax he imposed on citizens for defense. However, the military features of Leuven’s wall such as anchor towers, arrowslits etc cannot date before the 1200s, making this estimate too early. It is now generally accepted that Leuven’s first city wall was built by Henry I (Henrik), the first Duke of Brabant (1190-1235). He also abolished his father’s defense tax in 1233.

Constructed with layers of sandstone from nearby Diegem and Zaventem and ironstone, the first defense wall was roughly 2,740 metres long with 31 watch towers, 11 city gates and 2 water gates.

The wall measures 1.70m thick and rests on a series of underground arches. On the field side, the wall rises to about 5m tall. On the inside, a continuous series of arches supported a three-foot-wide walkway. The wall had arrowslits that were reduced on the outside to a narrow opening of 90cm high and 5cm wide.

However, as the city grew rapidly in size, a second (outer) more impressive defence wall was built in 1357, rendering the inner wall somewhat redundant. But the inner wall and gates were not immediately torn down. Most of it only disappeared in the 18th and 19th centuries. Even so, we see more of Leuven’s inner city wall today than the more recent outer city wall. Very well-preserved remnants of the 12th-13th century wall can still be seen in the City Park, as well as in the Refugehof, the Handbooghof, in the Redingenstraat behind the Irish College, and on the Hertogensite. The outer city wall and gates were torn down completely in the 19th and 20th centuries to become today’s ring road around the city.

Below is the list of the gates of Leuven’s first city wall starting from the north going eastwards:

- Steenpoort

- Heilige-Geestpoort

- Sint-Michielspoort

- Proefstraatpoort

- Wolvenpoort

- Redingenpoort

- Broekstraatpoort/Liemingepoort

- Justus Lipsiustoren-Janseniustoren*

- Minderbroederspoort

- Biestpoort

- Minnepoort

- Borchtpoort

- Sint-Geertruisluis*

*water gates.

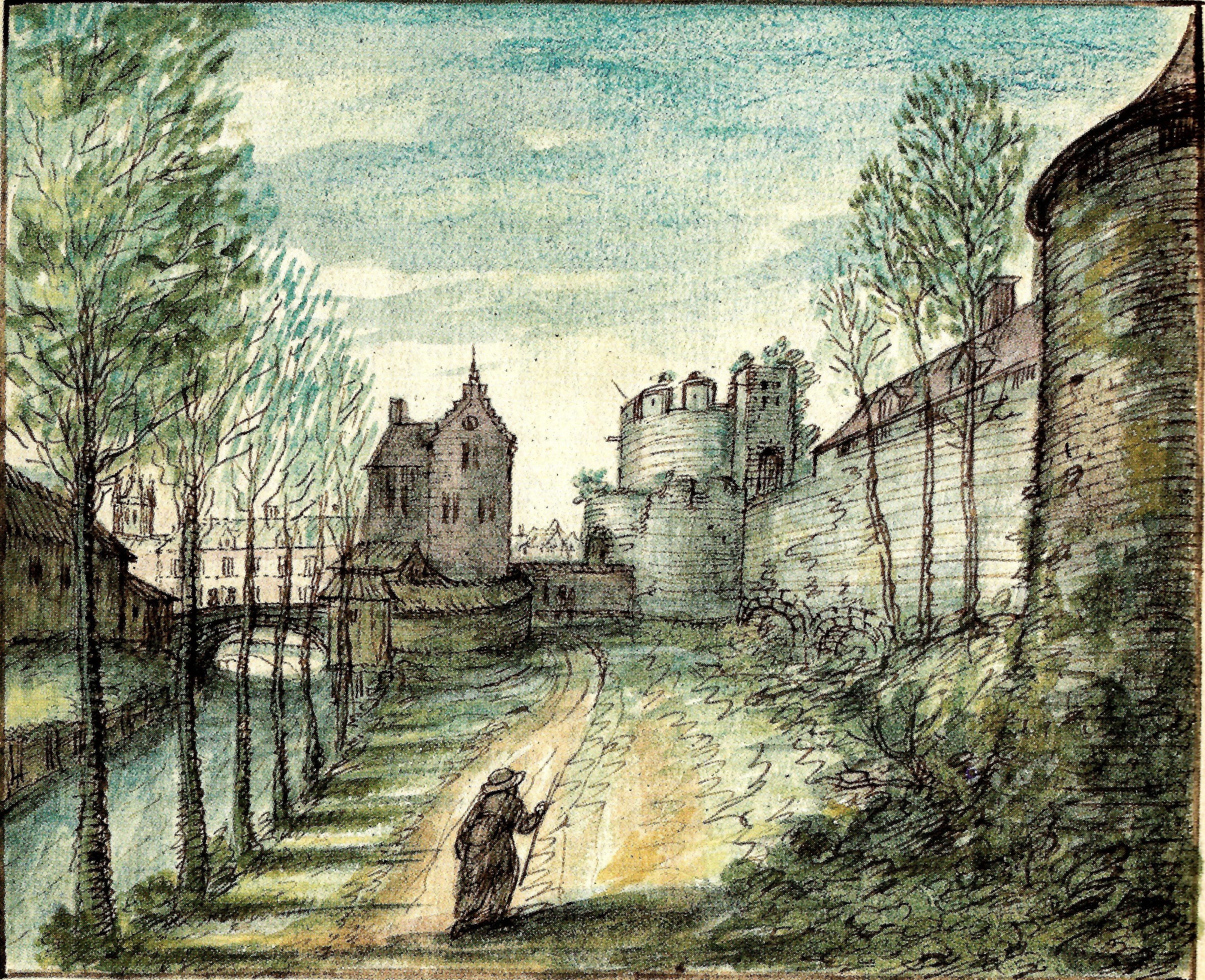

How did the Biestpoort look like?

There is only one accurate sketch of the Biestpoort from the Middle Ages, from the extra-muros perspective. The city gate is flanked by two semi-circular towers, and the whole structure rises two storeys high. The Biestpoort’s roof was of equal height for the centre gallery and the two towers. The wooden shutters of the windows were half open to allow for shooting from inside the gate at invaders. The gate opened onto a stone bridge that stretched across the River Dijle that formed the moat. On either side of the gate was a trapdoor, for when the gate was closed and enemies were approaching, one could still escape to the river banks along the city wall.

Above the gateway was a statue of the Holy Virgin Mary, which was lit up at night.

What's so special about this place?

The Village of Ter Biest

As explained in the post about the Sint-Jacobskerk (St James’ Church), there once was a village called Ter Biest located outside the city gate of Biestpoort, which was the reason for the gate’s name.

Situated today on the site of the Sint-Jacobsplein just outside the church, “Ter Biest” simply meant “At Biest“. The word “Biest” is a common toponym in the Low-Frankish regions of the Netherlands, referring to open outdoor spaces such as meeting places or village squares covered with rushes. In Modern Dutch, the word for rush is “veldbies” or “rus“. In the Middle Ages, fresh rush was strewn on earthen floors to keep them dry and clean.

The name “Biest” shows that the Voer Valley (east of the current Kapucijnnenvoer/Fonteinstraat) used to be covered in rushes.

The Oldest Street of Leuven

Also explained in the post about the Armenschool voor jongens (School for poor boys), the street on which the Biestpoort was located called the Brusselsestraat today was originally in the Middle Ages divided into three sections:

- ‘Steenstraat‘: from the Grote Markt to the inner city gate of Biestpoort

- ‘Bieststraat‘: from the inner city gate of Biestpoort, pass the Sint-Jacobskerk to the ‘Blauwen Hoek‘

- ‘Wijngaardstraat‘: from the ‘Blauwen Hoek‘ to the original Wijngaardpoort

The reason why ‘Steenstraat‘ (Stone Street) was named so, is because it was the first paved street of Leuven.

Possibly one of the oldest streets of Leuven, the Steenstraat is historically significant because it was most likely part of a Roman highway in the Gallo-Roman period.

The Rise and Fall of Pieter Couterel (1320-1373)

Once you pass the Biestpoort, the first street on your right is today called the Pieter Coutereelstraat.

In the Early Middle Ages, this place was called the “Korten Bruul” (the Short Bruul) as opposed to the “Langen Bruul” (the Long Bruul) which is today’s Brouwersstraat along the city park Den Bruul. In the 1800s the street took on very briefly the name of Caetspelstraat after the house on the corner called “Het Caetspel” (The Cat’s Game). But in 1895, with the extension of the street, the name was changed to Pieter Coutereelstraat.

So who was Pieter Counterel/Coutereel?

Whilst he was not of noble birth nor of wealth, Pieter Counterel became ‘Meier‘ of Leuven in 1348. His appointment by the Duke of Brabant Jan III showed that the Duke rewarded those who merited it. Back then in the Duchy of Brabant, the position of ‘Meier’ did not refer to the position of English word ‘Mayor’ although they are of the same Latin origin. A ‘Meier‘ was a director who served a nobleman and helped him administer certain taxes and presided over the local courthouse. When Pieter Couterel bought over the title of the Lord of Asten from Hendrik van Stakenborg, the Duke generously granted him the permission to do so.

But in 1360, Pieter Couterel led a popular uprising against the city council.

As explained about the Seven Clans of Leuven in the posts about the Redingenpoort and Broekstraatpoort, the city council used to be occupied only by nobility and only the nobility belonging to the Seven Clans. With the bad blood existing between Couterel and the nobility since his appointment as meier, Couterel stormed the council together with the craftsmen to protest against the dire economic situation due to the crisis in the cloth industry. He occupied the city hall and held the noble aldermen captive, and declared himself Lord of Leuven, and at the same time, that representatives of craftsmen should also sit in the city council.

The revolt lasted nearly two years with no peace in sight. One day, the nobility fled Leuven and Counterel filled the power vacuum by appointing himself the “Burgermeester” (mayor, but ‘master of the citizenry’). He then minted coins to raise money, but the profits were nowhere to be seen. By this time, the craftsmen were as angry as before, leaving Pieter Couterel without the popular support he had before.

The nobles who fled Leuven went to Duke Wenceslaus I of Brabant, Luxembourg and Limburg, who ordered the city gates to be opened for the return of the aldermen. Coueterel fled to Tervuren with 70 knights who remained loyal to him. For fear of a respite from the nobility, Counterel retreated to his castle in Asten where he plotted his return to no avail. By 1364, Pieter Couterel had his title of the Lord of Asten removed from him by the Duke, and was banished from Brabant. When he was allowed to return to Leuven in 1369, he was disgraced and penniless, and died impoverished and alone.

Today, there is a statue of a defiant-looking Pieter Couterel on the square called Ferdinand Smoldersplein, directly opposite Leuven’s courthouse, to commemorate the folk’s hero.

The Storming of the Biestpoort in 1360

So what has the Biestpoort to do with Pieter Couterel?

Before the Storming of the Bastille by the French revolutionaries in Paris on 14 July 1789, Leuven had already done it in 1360!

Since the 14th century, the Biestpoort also served as a civil prison and a torture chamber. In 1340, there was a number of textile craftsmen who were already imprisoned there and subjected to cruel tortures. When Pieter Couterel led the revolt in 1360, the Biestpoort was stormed by the uprisers to release the prisoners held there for the two decades. Notwithstanding, the rebels destroyed the entire city gate.

In 1382, more than a decade after the revolt, the city had to rebuild the entire Biestpoort because the damages were just not reparable.

Burnt by the English in 1743

The new Biestpoort once again as a civil prison in the 15th century. As attested by records dating from 1469, the underground dungeons had no stairs. Prisoners were lowered by means of an iron chain pulley.

By the 17th century, the Biestpoort was fortunately turned into lodgings for passing soldiers, which spelled nothing but trouble. During what is today called the the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748), France, Prussia and Bavaria, backed by England, the United Provinces of the Netherlands, and Hanover – called the Pragmatic Allies attacked the Habsburg Empire under the pretext of the right of Maria Theresa to succeed her father Emperor Charles VI as the next Habsburg ruler.

On 22 November 1743, the English Regiment of Handasyde which spent the night before in Biestpoort set it to fire once they were leaving the city. Not only the roof and interior were engulfed in flames, the fire also destroyed the roofs of two houses beside it.

Yet again, the Biestpoort was renovated in 1744 and again made available to passing troops. The idea to revert it back to being a civil prison was floated by Mayor Schotte in 1776, supported by the magistrate in 1778.

But in 1818, the government decided to use the much larger outer city gate of Diestsestraat as the central prison. This in turn made the Biestpoort redundant, as the function kept it far longer than all the other inner city gates of Leuven. By the next year in 1819, the Biestpoort was completely demolished.

The Handbooghof: ‘one of the most picturesque sites of Leuven’

The stretch of the 12th century city wall with watch towers that runs along the River Dijle between the Minnepoort and the Biestpoort is known today as the Handbooghof (Longbow Court).

19th century city archivist and historian Edward van Even called it “one of the most picturesque sites of Leuven” and indeed, it is one of the most beautiful historical spots where one can literally go back to the Middle Ages.

Please check out my post about the Minnepoort to read further about the Handbooghof.

You can still see traces of the guild house of the former Sint-Sebastiaan (St Sebastian’s Guild) on the city wall closest to the Biestpoort.

Current situation

The Biestpoort, having survived so many violent destructions in the course of the last few centuries, was the last of all of Leuven’s first city gates to be demolished. Today, the River Dijle was covered over with a supermarket built about it. The former historical site of Biestpoort is now but an insignificant part of the Brusselsestraat.

Sources:

“Louvain dans le passé et dans le présent“, Edward van Even, 1895

“De Leuvense Prentenatlas: Zeventiende-eeuwse tekeningen uit de Koninklijke Bibliotheek te Brussel“, Evert Cockx, Gilbert Huybens, 2003

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringmuren_van_Leuven

https://www.erfgoedcelleuven.be/nl/stadsomwalling

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/125406

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Biest

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juncaceae

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/themas/8258

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/themas/1035

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brusselsestraat_(Leuven)

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/themas/8178

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meier_(bestuur)

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.