ABOUT

The Broekstraatpoort (Brook Street Gate) was located in the Janseniusstraat before the bridge and not far from the Irish College.

Origin

The First and Inner Defence Wall of Leuven: After 1190

In the Early Middle Ages, Leuven was defended by a primitive fence that stretched from the Aardappelmarkt (modern-day Vital Decosterstraat) to the Redingenstraat, while an arm of the River Dijle formed a natural border.

By the 13th century, when the city grew to be the permanent residence of the Count of Leuven and Brussels, the need for a stronger defense bulwark became urgent. Historians have traditionally dated the construction of Leuven’s first defense walls to be between 1156 and 1165, during the reign of Count Godfried III, due to the yearly tax he imposed on citizens for defense. However, the military features of Leuven’s wall such as anchor towers, arrowslits etc cannot date before the 1200s, making this estimate too early. It is now generally accepted that Leuven’s first city wall was built by Henry I (Henrik), the first Duke of Brabant (1190-1235). He also abolished his father’s defense tax in 1233.

Constructed with layers of sandstone from nearby Diegem and Zaventem and ironstone, the first defense wall was roughly 2,740 metres long with 31 watch towers, 11 city gates and 2 water gates.

The wall measures 1.70m thick and rests on a series of underground arches. On the field side, the wall rises to about 5m tall. On the inside, a continuous series of arches supported a three-foot-wide walkway. The wall had arrowslits that were reduced on the outside to a narrow opening of 90cm high and 5cm wide.

However, as the city grew rapidly in size, a second (outer) more impressive defence wall was built in 1357, rendering the inner wall somewhat redundant. But the inner wall and gates were not immediately torn down. Most of it only disappeared in the 18th and 19th centuries. Even so, we see more of Leuven’s inner city wall today than the more recent outer city wall. Very well-preserved remnants of the 12th-13th century wall can still be seen in the City Park, as well as in the Refugehof, the Handbooghof, in the Redingenstraat behind the Irish College, and on the Hertogensite. The outer city wall and gates were torn down completely in the 19th and 20th centuries to become today’s ring road around the city.

Below is the list of the gates of Leuven’s first city wall starting from the north going eastwards:

- Steenpoort

- Heilige-Geestpoort

- Sint-Michielspoort

- Proefstraatpoort

- Wolvenpoort

- Redingenpoort

- Broekstraatpoort/Liemingepoort

- Justus Lipsiustoren-Janseniustoren*

- Minderbroederspoort

- Biestpoort

- Minnepoort

- Borchtpoort

- Sint-Geertruisluis*

*water gates.

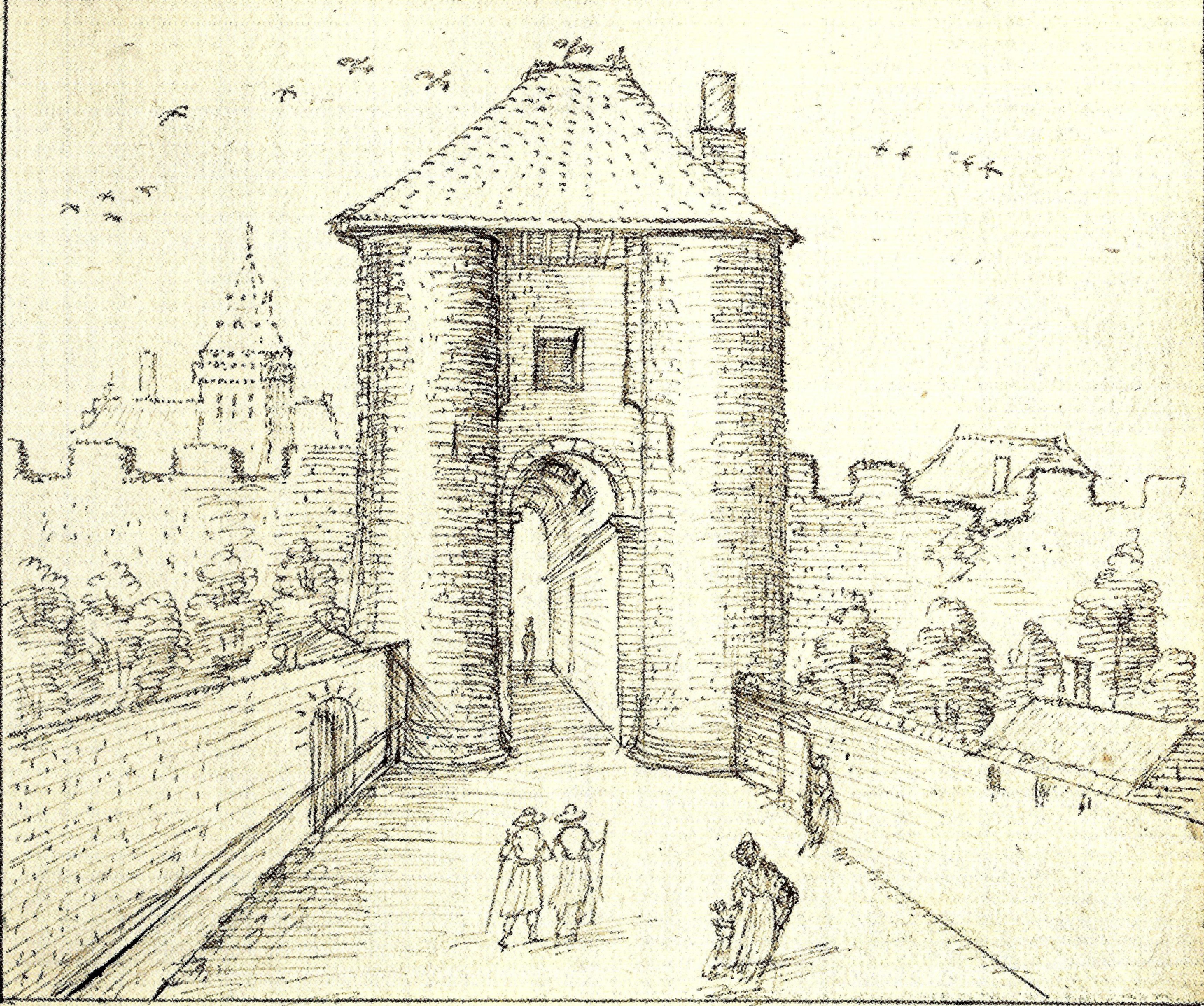

How did the Broekstraatpoort look like?

There was little mention by historian Edward van Even about the appearance of the Broekstraatpoort. Once built, it was renovated in 1366, 1383 and 1430, after which no works have been reported. Like the other inner city gates of Leuven, the Broekstraatpoort must have been in a very bad state by the time it was demolished in 1769.

What's so special about this place?

Broekstraat/Janseniusstraat

As mentioned in the post about the Sint-Joriskapel (Saint George’s Chapel), the current Jansensiusstraat runs from the Pater Damiaanplein all the way to the Kapucijnenvoer. In the Middle Ages, the street was known as the Broekstraat.

The word “Broek” means “low lying area that frequently flooded by ground water or by a nearby river“. It is related to the High German word “Bruch” and the English word “Brook“.

The name “Broekstraat” was first recorded in 1347, and shows that this area outside the city area used to be swampy and wet due to the rising water from the River Dijle.

The current name “Janseniusstraat” was named after the theologian Cornelius Jansenius (1585-1638), who used to be the President of the Hollands College on the site of the Hof van Uten-Lieminghe. The name change took place in 1977, after the fusion of suburbs of Kessel-Lo, Heverlee, Wijgmaal and Wilsele into Leuven. As these neighbourhoods all have their own Broekstraat, it was less confusing to eliminate at least one of them.

The Broekstraatpoort, when looked at from inside the city, bordered the Irish College on the left, and the Hof van Uten-Lieminghe on the right.

Once you step out through the city gate, you will come directly to a bridge across the River Dijle. This bank of the river used to be rather inhospitable and wet. A huge contrast to modern times, as the whole area around this part of the Janseniusstraat was completely destroyed by German air raids in 1944. This is the reason why all the houses from the bridge right up to the Kapucijnenvoer all dated from the 1960s-70s.

One of the Seven Clans of Leuven: Uten-Lieminghe

Just like the Redingenpoort nearby, the Broekstraatpoort became known as the Liemingepoort, as it bordered the Hof van Uten-Lieminghe – the city palace of the Uten-Lieminghe family.

The Hof van Uten-Lieminghe actually bordered two city gates: the Broekstraatpoort and the Waterpoort.

As the first Clan of Leuven, the Uten-Lieminghe/Liemingen family was one of the original Seven Clans of Leuven.

So who were the Seven Clans of Leuven?

According to 16th century historian Willem Boonen, who wrote about the the history of Leuven in 1593-1594:

“Hertog Carolus Calvus had de heer ridder Bastijn, bijgenaamd de Groote, aangesteld als graaf in Leuven. Bastijn huwde met een dochter van de graaf van Vlaanderen en had acht kinderen: één zoon, Volckaert, die in 900 bisschop van Luik werd, en ervolgens zeven dochters Plectrudis, Alpaidis, Betraert, Hildegarde, Ermgaert, Judith en Swane. Om het geslacht verder te zetten kon de graaf dus niet rekenen op zijn zoon en zocht hij bijgevolg voor elk van zijn dochters een waardig ridder als echtgenoot.”

Duke Carolus Calvus installed Bastijn the Great as the Count of Leuven. Bastijn married the daughter of the Count of Flanders who gave him a son, Volckaert who went on to become the Bishop of Liège in the year 900. The seven daughters – Plectrudis, Alpaidis, Betraert, Hildegarde, Ermgaert, Judith and Swane – were each wedded with a worthy knight in order to preserve the lineage.

The Seven Clans of Leuven were thus the knightly families of the sons-in-law of Bastijn. They were by order:

- Uten Liemingen [Uten-Lieminghe] (Ebroin, husband of Plectrudis/Plectrude)

- Van der Calsteren [van den Calstre] (Minard, husband of Alpaidis/Alpaïde)

- Van Redingen (Meys, husband of Betraert/Betrude)

- Van den Steene (Louis, husband of Hildegarde)

- Verusalem (Ebroin, husband of Ermgaert/Ermengarde)

- Gielis (Salomon, husband of Judith)

- Van Rode (Francon, husband of Swane)

Upon the death of Bastijn, each Clan shared his power equally in the form of council seals. Traditionally, only members of the Seven Clans could sit on the city council. Soon, the clans were split into two fractions: the “Colveren” vs the “Blankaerden“, who were constantly at odds with each other. There is no historical proof of these families being truly of noble descent, as recounted in this story. But they did exist, as they were the ruling class who wielded a lot of political and economic power in Leuven in the Middle Ages.

“The 1891 Flood of Leuven” by Constantin Meunier, ca. 1891-1900

The medieval name of Broekstraat to indicate the swampy low-lying area of this area was a wisdom we ought to have respected.

“On Sunday, 25 January 1891, a devastating flash flood hit Leuven: more than 141 hectares were under water, nearly half of the city. 59 streets with their 2325 inhabitants were flooded. Walls were warped and doors were broken by the sheer brute force of the rapidly rising water. The devastation was unimaginable.”

This was part of the report published by Leuven’s French-language newspaper ‘La Réforme‘ exactly a week after the disaster. The flood was said to have been caused by 55 days of immense frost followed by heavy rains, bringing the water level as high as two metres in some street.

At that time, Brussels painter Constantin Meunier was living and working in Leuven. Mayor Léopold Vander Kelen (1813-1895) led a rescue committee to rebuilt Leuven and to assist affected citizens. Apart from this huge operation, the city council gave Meunier the job to visually document the incredible impact of the flood.

Meunier himself was very much affected by the flood, as his workshop was completely destroyed. The city also would not pay him, as the payment was in the form of his rent for the workshop. Whatever the reason was, Meunier took 9 years to complete the oil painting.

“Overstroming van Leuven in 1891” was unveiled only in 1900. In the foreground, a man was in a rowing boat trying to bring his wife and child to safety. In the background, it was difficult to make out where the location was, except for the iconic (new) Sint-Michielskerk on the Naamsestraat. It is a very powerful image.

It took me sometime to locate the exact location where Meunier chose to depict the flood.

Much of it was imaginary as he was obviously not at a specific spot where the water level was dangerously high. But the spot where he chose to paint, appears to be across the Dijle bridge outside the Broekstraatpoort. You can clearly see the building of Irish College in the foreground painted as a workman’s house. The orientation of the Sint-Michielskerk is exactly the same, albeit now covered by trees. It would also have made sense that this was one of the most affected areas of the flood, because the “broek” on the left bank of the Dijle used to be the floodplain in the Middle Ages.

Current situation

While the Broekstraatpoort does not exist anymore, it is certainly worth visiting the spot, for both historic Irish College and the Hollandcollege. Also, cross the Dijle bridge and try to match the view with Constantin Meunier’s painting.

Sources:

“Louvain dans le passé et dans le présent“, Edward van Even, 1895

“De Leuvense Prentenatlas: Zeventiende-eeuwse tekeningen uit de Koninklijke Bibliotheek te Brussel“, Evert Cockx, Gilbert Huybens, 2003

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringmuren_van_Leuven

https://www.erfgoedcelleuven.be/nl/stadsomwalling

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/125406

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeven_geslachten_van_Leuven

https://nl.frwiki.wiki/wiki/Lignages_de_Louvain

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/themas/8241

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Janseniusstraat

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uten_Liemingen

https://artinflanders.be/nl/kunst/de-overstroming-van-leuven

https://vlaamsekunstcollectie.be/nieuws/constantin-meunier-overstroming-van-leuven-in-1891-collectie-m-leuven

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.