ABOUT

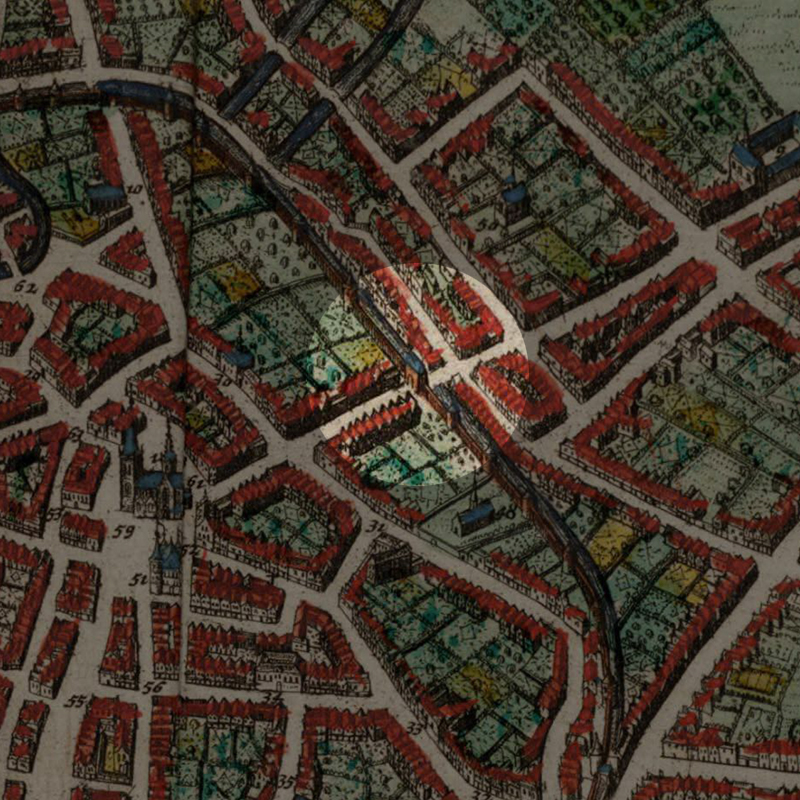

The Heilige-Geestpoort (Holy Ghost Gate) was one of the city gates of the first and inner city defence wall of Leuven. The gate was located on today’s Diestsestraat, at the junction with the Vital Decosterstraat.

Origin

The First and Inner Defence Wall of Leuven: After 1190

In the Early Middle Ages, Leuven was defended by a primitive fence that stretched from the Aardappelmarkt (modern-day Vital Decosterstraat) to the Redingenstraat, while an arm of the River Dijle formed a natural border.

By the 13th century, when the city grew to be the permanent residence of the Count of Leuven and Brussels, the need for a stronger defense bulwark became urgent. Historians have traditionally dated the construction of Leuven’s first defense walls to be between 1156 and 1165, during the reign of Count Godfried III, due to the yearly tax he imposed on citizens for defense. However, the military features of Leuven’s wall such as anchor towers, arrowslits etc cannot date before the 1200s, making this estimate too early. It is now generally accepted that Leuven’s first city wall was built by Henry I (Henrik), the first Duke of Brabant (1190-1235). He also abolished his father’s defense tax in 1233.

Constructed with layers of sandstone from nearby Diegem and Zaventem and ironstone, the first defense wall was roughly 2,740 metres long with 31 watch towers, 11 city gates and 2 water gates.

The wall measures 1.70m thick and rests on a series of underground arches. On the field side, the wall rises to about 5m tall. On the inside, a continuous series of arches supported a three-foot-wide walkway. The wall had arrowslits that were reduced on the outside to a narrow opening of 90cm high and 5cm wide.

However, as the city grew rapidly in size, a second (outer) more impressive defence wall was built in 1357, rendering the inner wall somewhat redundant. But the inner wall and gates were not immediately torn down. Most of it only disappeared in the 18th and 19th centuries. Even so, we see more of Leuven’s inner city wall today than the more recent outer city wall. Very well-preserved remnants of the 12th-13th century wall can still be seen in the City Park, as well as in the Refugehof, the Handbooghof, in the Redingenstraat behind the Irish College, and on the Hertogensite. The outer city wall and gates were torn down completely in the 19th and 20th centuries to become today’s ring road around the city.

Below is the list of the gates of Leuven’s first city wall starting from the north going eastwards:

- Steenpoort

- Heilige-Geestpoort

- Sint-Michielspoort

- Proefstraatpoort

- Wolvenpoort

- Redingenpoort

- Broekstraatpoort/Liemingepoort

- Justus Lipsiustoren-Janseniustoren*

- Minderbroederspoort

- Biestpoort

- Minnepoort

- Borchtpoort

- Sint-Geertruisluis*

*water gates.

How did the Heilige-Geestpoort look like?

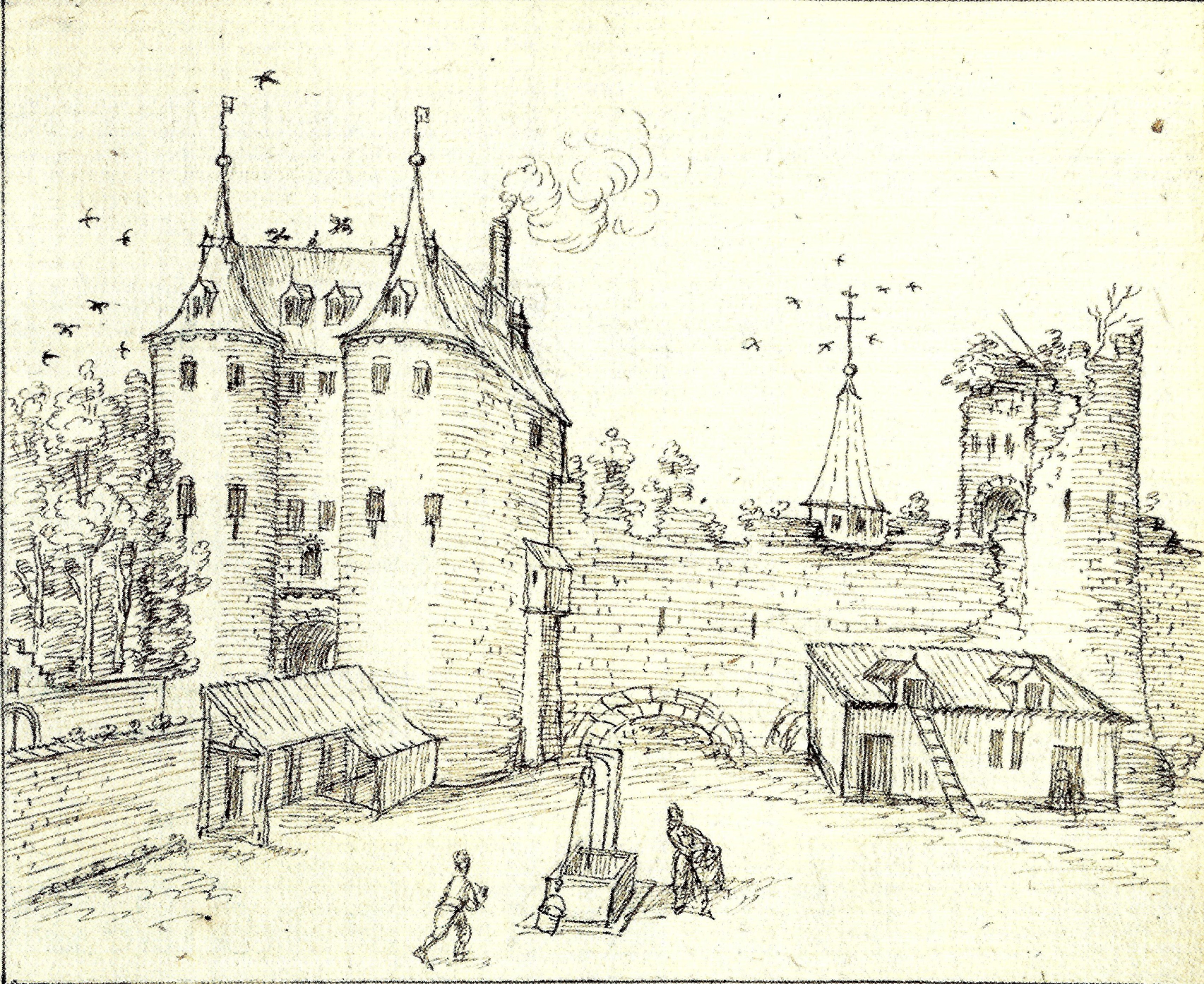

It is unclear how the original Heilige-Geestpoort looked like at the time when it was built. The original structure was destroyed in 1360 during a citizen’s revolt, which left it in ruins. It was not until 1383 that the city passed the order to have it rebuilt. The construction began the same year.

The new Heilige-Geestpoort was elegant: Two towers rose three levels high, and they met in the centre with a high gallery of equal height. Spiral roofs capped both towers. In 1464, city painter Hubert Stuerbout was commissioned to produce a painting of the Holy Virgin for the gate.

By 17th century, the Heilige-Geestpoort was occupied by one of the sergeants of the mayor, which points to its possible use for security. This led to its use as a prison in the following century.

What's so special about this place?

From the Village to the Holy Ghost

Before the street was named Diestsestraat (Diest Street), it was called the Dorpstraat, or Oppendorpstraat, after the village Oppendorp that was located just outside the city gate located on the same street. This was why citizens called the gate the Oppendorpe-Poorte (Oppen Village Gate) or the Dorpstrate-Poorte (Village Street Gate).

But the official name was the Heilige-Geestpoort (Holy Ghost Gate) because of the city’s charity administration being located nearby and named after the Holy Spirit, which also happened to house the city theatre.

The Citizen’s Prison: 1700?-1778

As mentioned in the post about Steenpoort, the city gate served as a prison.

With the use of Heilige-Geestpoort also as a prison, there seemed to be a chief difference between the two: The prison of Heilige-Geestpoort was reserved only for citizens of Leuven. Everyone else went to the Steenpoort prison, including Leuven citizens who were sentenced to torture or death.

In 1778, the city decreed the destruction of the Heilige-Geestpoort with the aim of widening the Diestsestraat, which by the following year, had completed disappeared without a trace.

Vital Decosterstraat

The city wall and moat that connected the Heilige-Geestpoort northwards to the Steenpoort and eastwards to the Sint-Michielspoort became a street which nowadays is called the Vital Decosterstraat, after Leuven’s mayor from 1901-1904 – Félix Vital Decoster.

The eastern part that linked to the Sint-Michielspoort ran through the former gardens of the Great Crossbow Guild (Grote Gilde van de Kruisboog) and then the back of the compounds of the Convent of the Clarisse (Clarissenklooster) on today’s Ladeuzeplein. When a street was carved out in 1801 under the French Occupation, it was named Marengostraat after Napolean’s Italian victory in the Battle of Marengo. This is the reason why the bar in the junction is called Café Marengo.

The northern part of the street that linked to the Steenpoort actually existed already in the 14th century as a footpath called the Bakeleynstrate. The “Bakelein” was actually the stream that flowed from outside the Steenpoort and stopped outside the Heilige-Geestpoort, and it served as the moat for the first city wall. The moat was first dammed in 1785 and then filled up in 1838, when the path broadened to become an actual street. This was renamed Weezenstraat (Orphans Street), or in folk’s tongue, the Weezenberg (Orphansberg).

Right of the Heilige-Geestpoort, was once the former house of the humanist Juan Luis Vives (Johannes Ludovicus Vives) (1493-1540), that was also along the Dieststraat.

The name of the house was called “Tweebronnen” (two sources) supposedly referring to the two springs in his garden. Vives took them to refer to Greek and Latin, the two linguistic foundations of humanistic knowledge at that time.

The modern-day public library on the Diestsestraat built on the former Convent of the White Sisters (Wittevrouwenklooster) is named after his house, although the convent was actually located beside it.

One part of the house was sold to Jesuits where they set up their first monastery in Leuven in 1560-1595, before they left for a larger establishment along today’s Naamsestraat. The first orphanage of Leuven was founded here in 1636. The Vivés house functioned in the 17th century as a refuge house and college for the novices of the Abbey of Floreffe and from 1718 to 1756 as a refuge house for the monastery of ‘s Hertogeneiland near Gempe (Sint-Joris-Winge) called the Godshuis van Gempe (Hospice of Gempe). Another part of the Vivés house stood the first seat from 1607-1621 of the Order of Discalced Carmelite Sisters (Klooster van de Ongeschoeide Karmelietessen) before moving to the Tiensestraat. The Irish Pastoral College (Iers Pastoraal College) then took over the property from 1623 until its abolition in 1797.

At house number 29, right up until the early 2000s, there were traces of 18th century remains of the Godshuis van Gempe. But sadly, nothing remains today.

At house number 25, the huge 20th-century mansion on the corner of Diestsestraat has a very dark history. On its facade is a small plaque that reads:

“Dit huis werd door de gestapo opgevorderd in 1943-1944. Leden van het verzet werden er gemarteld en daarna weggevoerd.

This house was possessed by the gestapo in 1943-1944. Members of the resistance were tortured here and brought away thereafter.”

This was the gestapo office for torture and questioning during the Second World War.

Current situation

The next time you go shopping on the Diestsestraat, and when you step onto the rainbow zebra crossing on the Vital Decosterstraat to continue your way towards the city centre, think of yourself crossing the drawbridge and entering the Heilige-Geestpoort in the 12th century. Try to take a break from your shopping, and explore the houses along the Vital Decosterstraat to experience the history of Leuven.

Sources:

“Louvain dans le passé et dans le présent“, Edward van Even, 1895

“De Leuvense Prentenatlas: Zeventiende-eeuwse tekeningen uit de Koninklijke Bibliotheek te Brussel“, Evert Cockx, Gilbert Huybens, 2003

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringmuren_van_Leuven

https://www.erfgoedcelleuven.be/nl/stadsomwalling

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/125406

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/themas/15120

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.