ABOUT

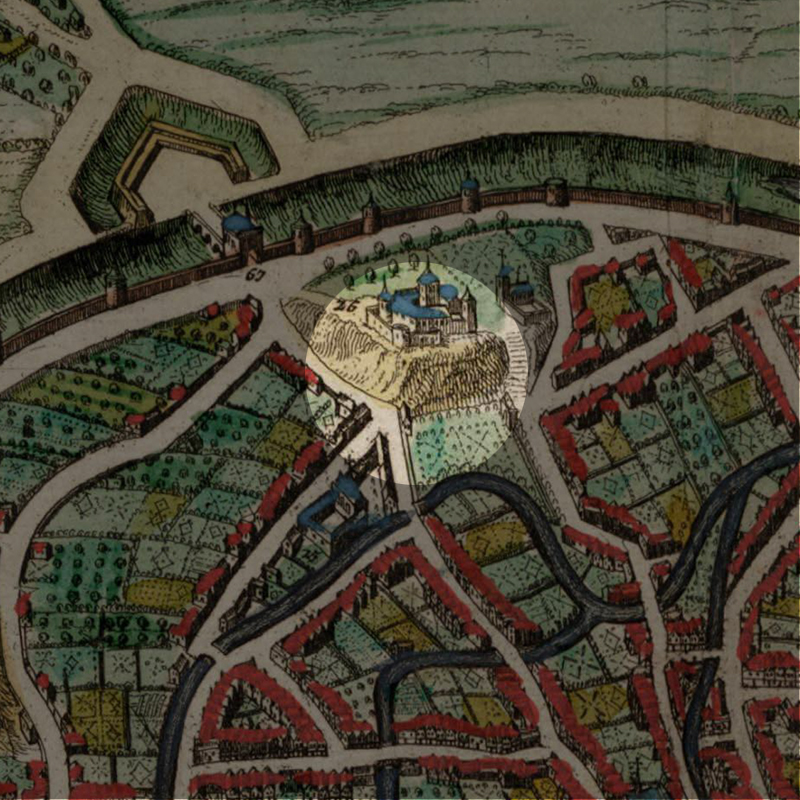

Located at the northern tip of Leuven, within the second and outer city wall and east of the city gate Mechelsepoort, the Keizersberg is a medieval fortified hill that currently houses a Benedictine monastery, a public park and an emblematic giant statue of Queen Virgin Mary with baby Jesus that overlooks the city. Keizersberg is one of the most important historical sites of Leuven, that used to be the location of the Castle of Leuven, and a Knight Templars’ outpost. The hill itself is part of the southern hills of the Hageland, that extends west of the city.

Origin

The origin and name of the Castle of Leuven (known as the “Burcht“) and the hill itself are shrouded in mystery. Not many inhabitants of Leuven know its exact origin.

Who built the Castle of Leuven?

Local traditions claim the Keizersberg and its castle date back to the year 50 when Julius Caesar conquered the area. Others claimed the Frankish leader, Arnulf of Carinthia, built it after defeating the Vikings (this has been located by recent historians to be in the Groot Begijnhof). Leuven historian Edward Van Even claimed in 1895, that it was built by the first Count of Leuven, Lambert I with the Beard, as a second residence before he died in 1095 and after he has built the Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-ter-Predikherenkerk on his estate, ’s Hertogeneiland (modern-day Sint Pietersziekenhuis and Hertogensite).

It is only until recently, that historian D Amand wrote in 2000-2003, that the construction of the castle is that of a “fortified round castle“, which is clearly an import from the Middle East. Judging from the leftover supporting ramparts which look exactly the same as the first and inner city walls, we can safely assume the Castle of Leuven was built by Hendrik IV Count of Leuven (1165-1235) who later became Hendrik I Duke of Brabant.

Hendrik I must have built the Keizersberg Castle after 1198 when he returned from the Crusade and saw the opportunity to show off his newfound fame and political might. The first city walls were built after 1161, so the Castle would have been a nice place of residence that is more exclusive than the Ducal estate ’s Hertogeneiland but still within the city walls.

Soon after the Castle was built, it was destined to never reach the display of power that Hendrik I intended. Instead, it went into a gradual centuries-long decline.

First of all, Duke Hendrik I was succeeded by his son Hendrik II, who in turn was followed by Jan I. At that time, Leuven was the capital of the Duchy of Brabant, but Jan I resided more and more in the Palace on the Coudenberg in Brussels. In 1267 when Jan I became the Duke of Brabant, he moved the Duchy’s capital to Brussels.

As with all castles whenever the owner is not around, it is kept by an innkeeper called the “kastelein“, some sort of “castle minder”. The Castle of Leuven was almost always unoccupied except by the kastelein. But there were notable occupants from time to time:

- In 1339, King Edward III of England and his wife Filippina of Henegouwen spent the winter there;

- Duchess Johanna of Brabant and her husband Duke Wenceslas I of Luxembourg (grandson of Jan I) stayed there in 1375-1377 and gave it a slight freshening up;

- From 1380 to 1389, it became the Ducal mint;

- In the 15th century, it became the meeting hall of the States of Brabant;

- In 1488, the Castle received a visit by Holy Roman Emperor Frederik III, which was a very great honour back then;

- Duke of Burgundy Jan IV and his brother Filips van Sint-Pol turned it into a tournament and party venue.

The Castle experienced a brief meltdown when Mayor (“Meier“) Pieter Coutereel ganged up with Leuven’s merchants and revolted. Coutereel locked up the city’s nobles in the Castle in 1360 and proclaimed himself “Heer” (Lord) of Leuven. Duke Wenceslas I managed to evict Coutereel in 1363 and he fled to Tervuren.

The Real Caesar of Keizersberg

In fact, the name “Keizersberg” (Mount Caesar) was not named after Julius Caesar, but after a more recent one – Habsburg Emperor Karel V (1500-1555). Born in Ghent, Karel V was the last ruler to have lived in the Castle of Leuven. Together with his sisters, child Karel V moved into the castle on 21 June 1504. Under the tutorship of Adrianus Floriszoon (later Pope Adrianus VI), Karel V spent several seasons in his Leuven residence until 1510. According to several sources, the child had a zoo with “cows, camels and a bear”. Because of his imperial presence, the Castle got several upgrades, such as a new dining room in 1518, a new roof for the water well in 1530, and a painting of Virgin Mary in the royal chapel in 1552 by Pierre van der Hofstad. Until the year before he died, the Castle of Leuven was constantly renovated and repaired regardless whether the Emperor was there.

The name “Keizersberg” certainly referred to Emperor Karel V but it was not in common usage, until the 19th century.

In the local folk’s lingua, the castle had always just been called “de burcht“, while the hill itself was called “Bolleberg” or “Boelenberg – meaning “bulwark hill”. During the French Revolution, it was briefly called “Le Mont de Bellevue“, after which it was called “Château César” and the Dutch version “Keizersberg” only appeared around 1845.

The Temple of Diana

Under the hill, roughly where the “Tramweg” now begins, were two buildings worth mentioning. Since 1362, a building called “Boutsvort” served as a sort of kennel for the castle, where hunting dogs were housed. Beside it, was a Romanesque chapel called “Templum Dianae“, or Temple of Diana. As the Roman Goddess was also the goddess of hunting, it was likely the chapel was somehow linked to the kennel. In any case, Boutsvort burnt down on 21 December 1591, while the Temple of Diana was demolished in June 1769.

The Castle was no more

By the 18th century, the Castle of Leuven was in such a dilapidated state, the last kastelein took office in 1721 but not thereafter. On 16 May 1782, Habsburg Emperor Jozef II gave the order to break down the Castle and put on sale whatever that was valuable. The ruinous Burcht was sold mostly as building material. Only the water well and some of its rampart remain up to this day.

After the Castle was broken down, the site briefly served as a windmill until 1810.

In 1889, the grounds were sold to the Benedictine monks of Maredsous who wished to set up a study house in Leuven for their apprentices pursuing theology in the University of Leuven.

Instead of building directly on the former Castle site, the abbey was built away from the rampart and occupies the space all the way up to next to the city gate Mechelsepoort and against the city wall (today the ring).

While the abbey was spared by the First World War, it was seriously damaged in the Second. The roof, the windows, the church organ and much of the cloister were destroyed and had to be rebuilt. Today, like all religious institutions, the abbey is facing financial difficulties maintaining such a big site.

What's so special about this place?

The Knights Templar Outpost

Located east of the Castle and on the same hill, used to be a Knights Templar outpost called a “commanderij“. The outpost was built at the end of the 12th century or beginning of the 13th century, initiated by Count Godfried III. The commanderij was tasked with caring for and protecting pilgrims going to the Holy Land.

In the folk’s tongue, this part of the hill is called “Wolvenberg” despite being the same hill as the Castle (whose side is called the “Boelenberg“).

The commanderij also had a chapel, dedicated to Saint Nicholas. Both north and south of the outpost were vineyards.

With the abolition of the Templar Order by Pope Clement V in 1312, the outpost was given to the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, or Knights Hospitaller in short. The Knights Hospitaller dedicated the chapel to Saint John the Baptist. By the 16th century, the Knights Hospitaller seemed to have deserted the site. The building was already offered/rented to exiled English Jesuits and then from 1625 to 1650 to Irish Dominicans.

During the French Revolution, the outpost was broken down and sold. Between 1801-1802, it was turned into a farmhouse but a wing was the only surviving structure of the Knights Templar Outpost.

During the Nazi invasion, the farmhouse was completely destroyed together with major parts of the abbey in the bombardments of 11 and 12 May 1944.

Today, you can still see some remains of the farmhouse’s walls, and somewhere underneath is the foundation of the Knights Templar chapel.

A really interesting tale recounted by Frederic Hecq in his book on the Keizersberg is that Knights Hospitaller’s Sint-Jan de Doper (St John the Baptist) chapel was a site of pilgrimage for Leuven’s mothers.

Apparently, babies stopped wailing once they were brought into the chapel.

In the local tongue, a painting featuring St John housed in the chapel was known as “Janneke de grijzer“, and “grijzer” means “crybaby”. The painting was the only relic saved from the chapel when it was sold off, and was for a moment stored in the Sint-Kwintenskerk. That was stolen, and was replaced by a replica. And again, the replica was also stolen.

The Statue of Virgin Mary

In 1889, the first 14 monks from the Abbey of Maredsous arrived in their new abbey, the Abbey Keizersberg of Leuven officially known as “Abbatia Reginae Coeli de Castro Lovaniensi“, under the leadership of their abbot, Dom Robert de Kerchove.

Dom Robert clearly wanted to continue the royal theme of the site. The new abbey chose as its insignia a lily with a crown (Regina Coeli) and the words “Veni coronaberis” – “Come and thou shalt be crowned“.

The patroness of the abbey was Virgin Mary, “Queen of the Heavens” and Dom Robert commissioned a giant crowned Virgin Mary with baby Jesus by well-known Leuven sculptor Benoît Van Uytvanck. On 30 July 1906, the statue was erected. It replaced the giant vase, that was placed on the site of the Castle on the edge of the cliff overlooking the city.

The “Mariabeeld” is to Leuven what Christ the Redeemer is to Rio de Janeiro.

On a clear day, it is clearly visible from the Mechelsestraat and from the Bruulpark.

Current situation

A historical site in danger of collapsing

Now a public park, the whole Keizersberg apart from the private area of the abbey is open to the public in the day. It is a perfect lookout spot for a panoramic view of Leuven and a quiet spot to clear one’s thoughts.

But Keizersberg is facing unprecendented challenges.

First of all, the abbey is on the verge of bankruptcy. With little state assistance, low levels of religiousity, little interest from the public, the building is too big for a handful of monks to maintain, both physically and financially. Although rooms were rented out to students, the income is insufficient to prevent the abbey from falling into further disrepair.

Secondly, the 12th century ramparts are falling apart. After centuries of neglect, the stones can barely hold together. Yet this is all we have left of the Castle of Leuven. In the last century, someone had the “brilliant” idea of planting acacia trees on the rampart, and their roots are now pushing the stones out. A forthcoming disaster is certainly the fall of the giant statue of Virgin Mary. She is literally standing on 12th century structure that can crumble at any moment.

The third disaster is the imminent collapse of Keizersberg itself. In the 1840s, a certain engineer called Tarte and an English company were tasked to dig through the Keizersberg and work on Leuven’s electric tram network (hence the traces of tracks, and the names “Tramweg” and the nearby “Engels Plein” where the station was supposed to be). The second “well” you see in the middle on the Keizersberg is not a water well, but an airvent for the tram. But the trajectory under the hill was abandoned and no one knew if the tunnel was filled up again. Apparently it was not. With a century of rain and erosion, the tunnel has probably collapsed, which would next lead to holes forming on the surface. This has already happened. A 2-metre long hole was found recently in the cemetery of the abbey, located east of the former commanderij. To this day, no one knows how deep the hole really is. If this continues, the soil will collapse along the trajectory of the tunnel leading to a massive disaster.

Sources:

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/42148

https://abdijkeizersberg.be/

“De Vloek op de Keizersberg”. Hecq, Frédéric. 2019: De Boeken Maker, Leuven.

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.