ABOUT

The Sint-Michielskerk (Saint Michael’s Church), which rests upon the inner city gate of Sint-Michielspoort (Saint Michael’s Gate) does not exist anymore. Yet this was one of the iconic sights and sites of Leuven, one of its Seven Wonders. Its former location is on the Tiensestraat – from the external façade of the Sancta Maria Leuven school, to before the entrance to the city park and the Herbert Hooverplein.

Origin

The First and Inner Defence Wall of Leuven: After 1190

In the Early Middle Ages, Leuven was defended by a primitive fence that stretched from the Aardappelmarkt (modern-day Vital Decosterstraat) to the Redingenstraat, while an arm of the River Dijle formed a natural border.

By the 13th century, when the city grew to be the permanent residence of the Count of Leuven and Brussels, the need for a stronger defense bulwark became urgent. Historians have traditionally dated the construction of Leuven’s first defense walls to be between 1156 and 1165, during the reign of Count Godfried III, due to the yearly tax he imposed on citizens for defense. However, the military features of Leuven’s wall such as anchor towers, arrowslits etc cannot date before the 1200s, making this estimate too early. It is now generally accepted that Leuven’s first city wall was built by Henry I (Henrik), the first Duke of Brabant (1190-1235). He also abolished his father’s defense tax in 1233.

Constructed with layers of sandstone from nearby Diegem and Zaventem and ironstone, the first defense wall was roughly 2,740 metres long with 31 watch towers, 11 city gates and 2 water gates.

The wall measures 1.70m thick and rests on a series of underground arches. On the field side, the wall rises to about 5m tall. On the inside, a continuous series of arches supported a three-foot-wide walkway. The wall had arrowslits that were reduced on the outside to a narrow opening of 90cm high and 5cm wide.

However, as the city grew rapidly in size, a second (outer) more impressive defence wall was built in 1357, rendering the inner wall somewhat redundant. But the inner wall and gates were not immediately torn down. Most of it only disappeared in the 18th and 19th centuries. Even so, we see more of Leuven’s inner city wall today than the more recent outer city wall. Very well-preserved remnants of the 12th-13th century wall can still be seen in the City Park, as well as in the Refugehof, the Handbooghof, in the Redingenstraat behind the Irish College, and on the Hertogensite. The outer city wall and gates were torn down completely in the 19th and 20th centuries to become today’s ring road around the city.

Below is the list of the gates of Leuven’s first city wall starting from the north going eastwards:

- Steenpoort

- Heilige-Geestpoort

- Sint-Michielspoort

- Proefstraatpoort

- Wolvenpoort

- Redingenpoort

- Broekstraatpoort/Liemingepoort

- Justus Lipsiustoren-Janseniustoren*

- Minderbroederspoort

- Biestpoort

- Minnepoort

- Borchtpoort

- Sint-Geertruisluis*

*water gates.

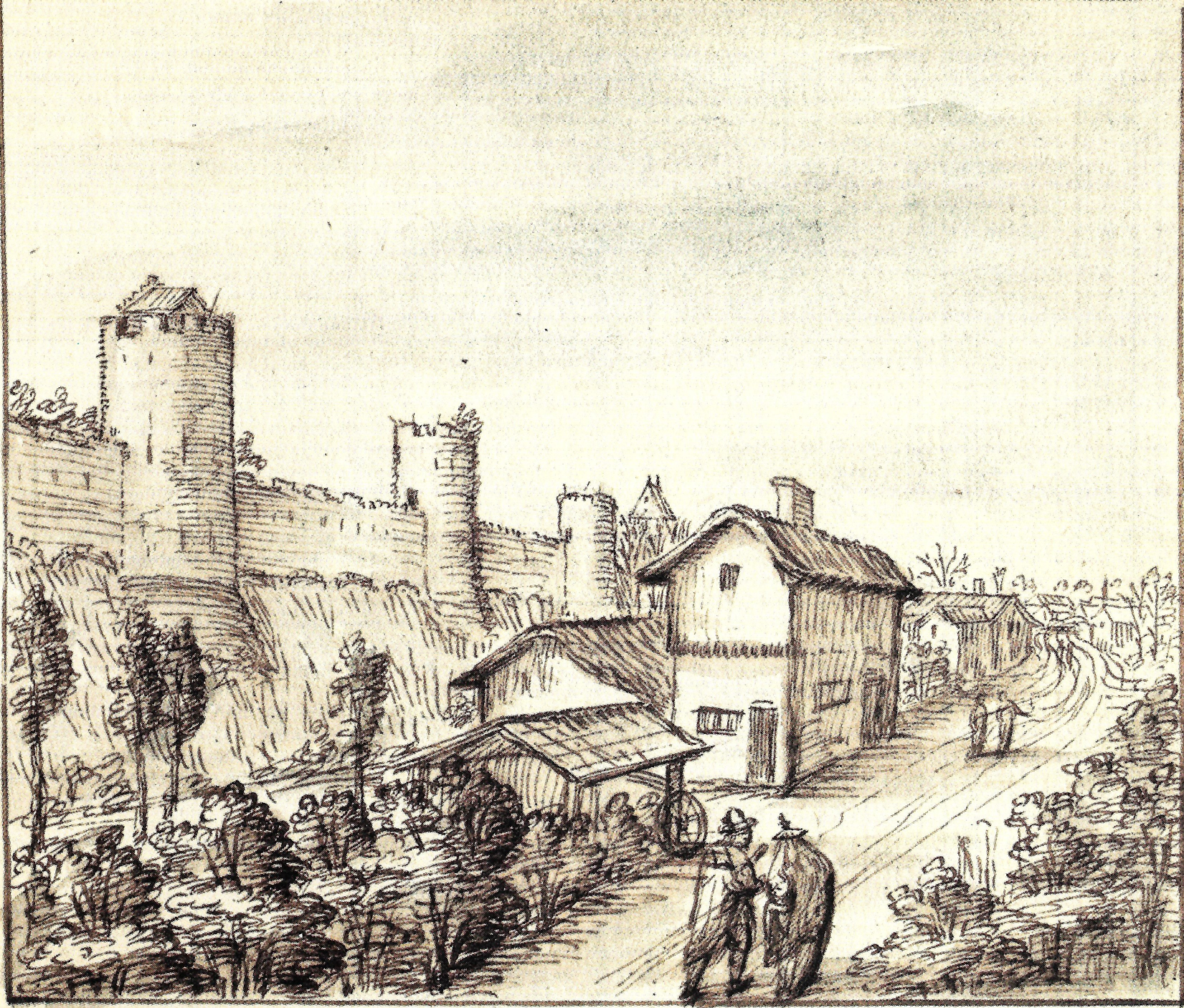

How did the Sint-Michielskerk/Sint-Michielspoort look like? Both a church and a city gate

The Sint-Michielskerk (Saint Michael’s Church) and the Sint-Michielspoort (Saint Michael’s Gate) were one single construction.

The romanesque Sint-Michielskerk, being above the city gate, was only accessible via a flight of stairs. The city gate itself was named after the church, but was also known as the “Hoelstraetpoort“, as the street that nowadays called Tiensestraat was then known as the Hoelstraete or Hollestraat. Under the gate was a dungeon, where the mentally ill were locked up. Next to the parish church was the cemetery on today’s Herbert Hooverplein.

In the 14th century, the church had to be rebuilt after it suddenly collapsed. With the reconstruction, its side chapels were further embellished and increased to five in number.

The tower of the church was a significant landmark back then. It served as a belfry for a while during the fifteenth century, as Leuven had never had a belfry. There were three bells in the tower, known as the “Dakklok” (roof bell), the “Sluitklok” (closure bell) and the “Wekklok” (wake-up bell). The last two were sounded when the Sint-Michielspoort closed and opened.

Leuven’s rich and famous were buried inside the church marked with tombstones, which led to its fame as one of the Seven Wonders of Leuven (see below).

In 1560, the Sint-Michielskerk was devastated by a huge storm which left it looking extremely gloomy thereafter. By the 17th century, houses were built right next to its cemetery, including the College of ‘s-Hertogenbosch.

What's so special about this place?

Why was the Sint-Michielskerk/Sint-Michielspoort one of the Seven Wonders of Leuven?

This is because it was the place where:

“De levenden lopen onder de doden.

The living walked under the dead.”

With the church above the gateway, it was indeed the most unique situation where people were going in and out of the city passing under the tombs that were housed in the church. By the 1770s, the church was in such a bad state that wooden planks were used to prop up the walls of the old city gate and the church on it.

Between 1778 and 1781, this Leuven wonder was broken down and flattened to the ground.

The church community was moved to the now empty Jesuit College on the Naamsestraat, as the Society of the Jesuits were banned in 1773. This is the present-day Sint-Michielskerk (Saint Michael’s Church), a Baroque church.

Current situation

Today, you can see some markings on the ground which the city had placed in order to mark where the gate/church was. It is currently on the site of the back entrance of the Sancta Maria Leuven school on the Tiensestraat, along the entrance of the Sint-Donatiuspark and on the Herbert Hooverplein.

The city walls in the Sint-Donatiuspark

Whilst you explore the spot which marks the former Sint-Michielskerk/Sint-Michielspoort, go into the city park in order to behold the remnants of the city wall, especially the watch towers, that used to connect directly to the city gate.

Sources:

“Louvain dans le passé et dans le présent“, Edward van Even, 1895

“De Leuvense Prentenatlas: Zeventiende-eeuwse tekeningen uit de Koninklijke Bibliotheek te Brussel“, Evert Cockx, Gilbert Huybens, 2003

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringmuren_van_Leuven

https://www.erfgoedcelleuven.be/nl/stadsomwalling

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/125406

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zeven_wonderen_van_Leuven#De_levenden_lopen_onder_de_doden

http://www.leuvenshistorischgenootschap.be/Nieuwsbrief%20LHG%202005-02_Herbert%20Hooverplein.htm

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/140040

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sint-Michielskerk_en_Sint-Michielspoort

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.