ABOUT

Hidden in the quiet street of Vlamingenstraat at the junction with Frederik Lintsstraat is the splendidly Baroque “Kapel van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Koorts” (Chapel of Our-Lady-of-Fevers). Today, the chapel is the interdisciplinary Documentation and Research Centre for religion, culture and society of the KU Leuven university, KADOC.

Origin

In Flanders Fields

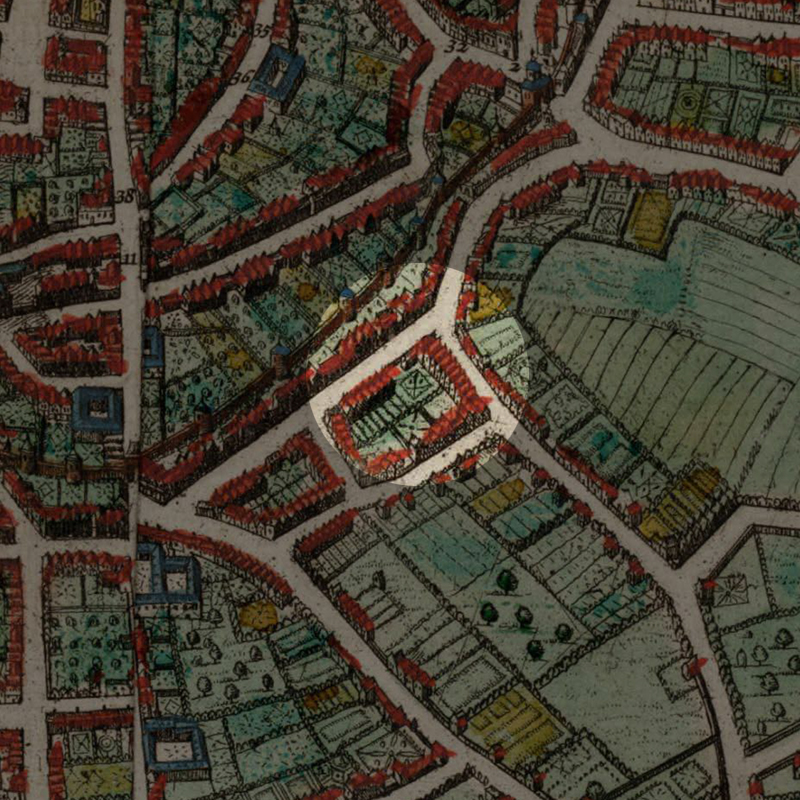

To talk about the origins of the neighbourhood in the “Kapel van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Koorts” (Chapel of Our-Lady-of-Fevers), we have to first start with the neighbourhood in which the chapel is located. Back in the early Middle Ages, this part of Leuven was located just outside the city walls, which today can still be seen in the Sint-Donatius city park. Persons of undesirable characters or those working in vice often had to live outside the city walls, and left in their own devices whenever invaders struck the city.

In the second half of the 13th century, a group of immigrants from the County of Flanders and formed their own extra-muros village, and so, the area became known as ‘Vleminckxveld‘ (Flemish fields).

One should be reminded that the real historic Flanders has little to do with the current political Flanders invented only in the late 19th century. The County of Flanders was ruled by its own Count, and its territory covered today’s East and West Flanders, the French Flanders region of France and the Zeelandic Flanders region of the Netherlands. The Duchy of Brabant, with its capital in Leuven, was a completely different country. Under the Treaty of Verdun of 843, Flanders belonged to West Francia while Brabant belonged to Middle Francia (later Lotharingia). This division continued throughout most of the history of the two states under Habsburg rule until the French invasion in 1795. Today, the Brabantian identity is largely forgotten, taken over by the awkward terms of ‘Flanders’ now referring to the whole Dutch-speaking region of modern-day Belgium and ‘Flemish’ to the people who live there and the various Dutch dialects spoken in Belgium. To know more about the rise of the political Flanders, check out my articles on ‘The Self-Identification of the Other: How Flanders came to be the Name of the Region Today‘.

Between the 12th and 15th century, the County of Flanders was renowned throughout Europe for its weaving industry. Yet because Flanders was under the rule of the French Empire, which was in constant combat with England, Flanders’ main source of wool, the collapse of the industry in the second half of the 13th century led to waves of Flemish migration into the Duchy of Brabant. This led to some of them settling just outside Leuven, not as welcomed guests but as undesirables.

The Miracle of the Immovable Statuette of Virgin Mary

The story began in 1535, when a female resident in the Vleminckxveld placed a wooden statuette of Virgin Mary in Pieta in the altar on the front of her house. That night, a group of (possibly drunk) students tried to remove the statue, but it refused to budge “like a block of granite”. This was hailed as a miracle. Henceforth, the statuette was hung on a tree in the neighbourhood, drawing veneration from far and wide. The earliest account of this story was written by Norbertine friar Augustine Wichmans in his “Brabantia Mariana tripartite” (1632). The statue has survived the centuries, and is now preserved in the Sint-Jozefskerk (St Joseph’s Church) in the Bogaardenstraat in Leuven.

The devotional attraction of the miraculously immovable statue was so great, that the pastor of the parish church Sint-Michielskerk gave his permission in 1540 to build a modest chapel for the Pieta statuette. the chapel then received the name of Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-van-de-Vlamingenstraat (Chapel of Our Lady of the Flemingstreet) or simply as Vleminckxkapel (Flemish Chapel).

Soon, the Flemish Chapel gained the reputation of a place of healing, especially for fever.

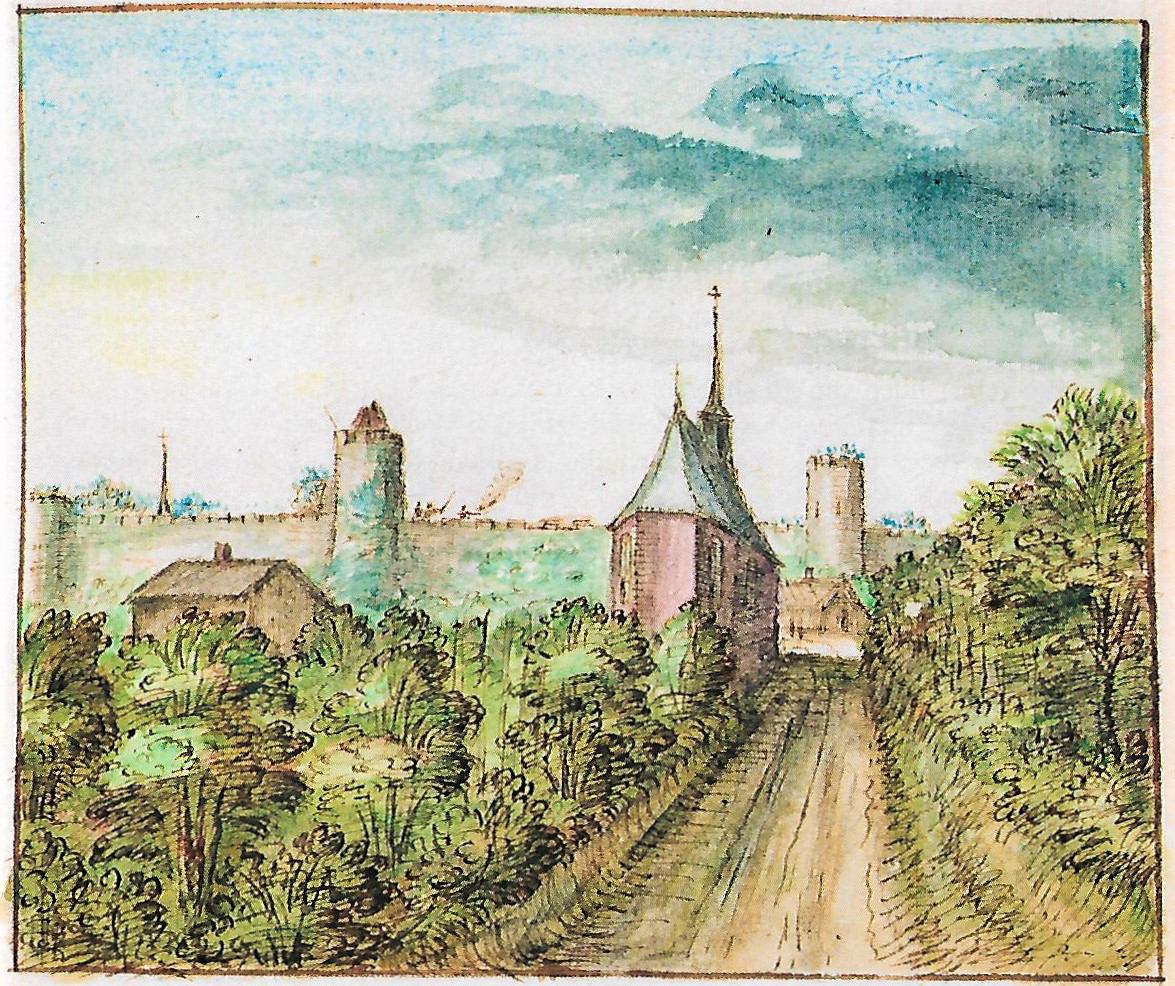

This reputation drew believers from not just the neighbourhood, but also from the whole city and the surrounding region. The number of devotees necessitated the construction of a bigger building in 1601. In 1603, the Archbishop of Mechelen, Mathias Hovius (Matthias van Hove), officiated this new chapel. A watercolour painting of this building can be found in the 17th century ‘Het Leuvens schetsboek’ (The Leuven Sketchbook), from the perspective of Flessenstraat (today’s Frederik Lintsstraat).

The theologians at the Leuven University were managing the chapel, and they were the ones who stimulated the devotion of Virgin Mary, making the chapel a site of pilgrimage. Under the supervision of Sint-Michielskerk, the chapel started its own brotherhood in 1643, who organised the yearly procession of the Virgin Mary devotion and open air masses, with the abbots from the nearby Abdij van Park.

The Slow Road to a New Chapel

On 8 October 1641, a large crowd gathered outside the chapel. Together with the magistrates of the city, the Marquise of Aarschot, Dorothea van Croÿ gave an audience to devotees of the Virgin Mary. Then, she laid the first stone of a new building that will accommodate even more pilgrims.

The cult of Virgin Mary in combination with her invocation to heal especially children with fever, was a huge success. By the 17th century, the chapel became known as Kapel van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Koorts to highlight its specific expertise.

Parents hang ex voto all over the walls of the chapel, often pictures and drawings of their sick children, in search of divine intervention to help them recover. The funds and support from the Marquise came at an opportune moment.

Yet works barely progressed in the years to come. In fact, the construction only started in 1700 and completely in 1705. The roof only came in 1733.

Despite all structural setbacks, the religious exploitation of worried parents never stopped. Desperate parents of sick children and grateful parents of healed children continued to adorn the walls of the chapel with paintings of their children.

What's so special about this place?

The Most Splendid Baroque Chapel

Many know of the famous Basilica of Our Lady of Scherpenheuvel in Belgium, being a major centre of pilgrimage for the worship of the Virgin Mary. Its majestic dome that rises above the horizon is an awe inspiring sight. Yet not many know that Leuven’s Kapel van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Koorts was exactly built with the same Baroque architectural concept: an impressive facade with a dominating dome for the adoration of the Holy Virgin.

When the chapel was finally completed in 1733, it soon became the favourite church of the city’s upper classes.

The beautiful sculpted and ornate facade exudes nothing but elegance. High above the main door was a Pieta sculpture, a highly stylised reference to the original miraculous statuette in the humble immigrant slum of Vleminckxveld. According to 19th century historian Edward van Even, “Leuven’s rich like the new chapel so much, that they did not miss its daily eleven o’clock mass, and they would arrive in their ornately gilded carriages decorated in red and blue damask fabric”.

But this flaunting of wealth and beauty did not last long. By 1798, under the French invasion, the chapel was put on auction, like many of Leuven’s religious buildings. Fortunately, one of the chapel masters called Van Hamme bought the building, thus prevented it from being demolished or sold off. In 1801, with Napoleon reaching an agreement with Pope Prius VII, the persecution of churches stopped and religious activities returned in Leuven.

And this time, quite miraculously, the original 16th century Pieta statuette of the Kapel van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Koorts eventually found its way back to its home in 1802.

In 1803, there was a reform of the parishes in Leuven. Formerly under the parish of Sint-Michielskerk, the Chapel became the new parish church, although still in the hands of the family of Van Hamme. The pastor of this new parish church, Van Rosse, found the portraits of thousands of deceased children too disturbing for his congregation, so he had them all burnt in 1825. Thus a huge part of the chapel’s history is lost forever. And in the years 1865-1871 the parish function was transferred to the newly built Sint-Jozefskerk.

The Monastery of the Franciscans

The Order of the Friars Minor were founded in 1209 by Francis of Assisi, hence the members are also known as the Franciscans. They established their first monastery here in Leuven by the Minderbroederstraat in the year 1231, until its dissolution by the French invaders by the end of the 18th century. Hence with the return of religion, the Franciscans hoped to reestablish themselves again in Leuven. By buying over the Kapel van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Koorts from the family of the chapel master who saved it, in 1871, the friars commenced their comeback.

The transformation of a devotional chapel to the Virgin into a monastery of Friars minor changed of course the nature of the place. The friars built somber buildings by and around the chapel to house local but also visiting brothers. Next to the devotional chapel, the monks built an adjoining chapel only for themselves. In 1882, architect Joris Helleputte was asked to design a Neo-Gothic expansion of the choir and Helleputte also expanded the space of the chapel. Most notably, a wall was built around the compound, such that only the facade of the chapel is now visible on the Vlamingenstraat, as is the case today.

The Kapel van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Koorts and the Monastery of the Franciscan Friars subsequently went through a tumultuous period of the two world wars as the rest of the population. The original Pieta statuette even had to go into hiding, replaced by a replica, to prevent it from being destroyed. By the 1970s, the monastery had declined and had to be wound up, together with the school they were running in the after-war years.

Current situation

In September 1987, the KU Leuven University bought over the Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Koorts, to house their the interdisciplinary Documentation and Research Centre for religion, culture and society, also known as KADOC.

The chapel and the monastery buildings are now used for exhibitions and public readings. Its underground spaces have been turned into precious repository of historical documents and artifacts.

Most crucially, the original statuette of Virgin Mary that started this all, has now found its permanent home in the new parish church of Sint-Jozefskerk in the Bogaardenstraat.

Another interesting point to note: despite the changes to the chapel made by the Franciscans, we are now (in the progress of) restoring this beautiful Baroque chapel to its original state, thanks to a photo taken in 1865 by Brussels photographer Edmond Fierlants before any of the side buildings were erected.

Many thanks to the exhibition organised by KADOC in 2016 and the publication written by Roeland Hermans for the additional insight.

Sources:

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/42133

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kapel_Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-ter-Koorts

http://www.tellyourphotostory.be/espace_test/exhibits/show/chapels-churches-leuven/kadoc

Hermans, Roeland, “Koorts op het Vleminksxveld – De kapel van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw ter Koorts en het klooster van de minderbroeders in Leuven”. 2016: KADOC, Leuven.

http://www.europeana.eu/portal/record/2032014/c6688572641a30361ae224fa09d8412a.html (Image)

Fierlants, Edmond, “De kerk van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-ter-Koorts van Leuven,” Photography Pilot (Image)

“Louvain dans le passé et dans le présent‘, Edward van Even, 1895 (Image)

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.