ABOUT

There is nothing left of Leuven’s original Capuchin Monastery (Kapucijnenklooster) which was founded in 1591 and destroyed by the French Revolution in 1796. As a major offshoot of the Franciscans, the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin (Kapucijnen) lived in poverty and modesty, and were much appreciated by Leuven’s inhabitants during their time there.

Today, the spot houses the “Hortus Botanicus Lovaniensis”, popularly known was the “Kruidtuin” – Leuven’s own Botanical Garden. It is one of the most beautiful and tranquil places in the city.

Origin

How the Capuchins settled in Leuven

The year was 1591. After successfully establishing themselves in Antwerp, Ghent and Brussels, the Capuchin friars thought of setting up shop in the desolate city of Leuven. Leuven, the mighty former city of the Duchy of Brabant, had fallen in bad times.

The plague of 1578-1579 had decimated three quarters of the population. 2000 houses had to be broken down and many streets broken up. The bodies were buried, and the remains of their houses were used as firewood. By 1598, there were only 6868 inhabitants left, of whom 610 were monks and nuns.

As always, human misery means great business for religious institutions.

The Capuchins also found themselves a generous donor by the name of Jacobus de Bay (Bajus) van Ath, who offered to buy them a piece of land near the River Voer within the city walls. But things did not begin well with an uncooperative seller.

The Haunting begins

The piece of land by the Voer had a single straw house on it, owned by a landlady who simply refused to sell it to Mr Bajus, for fear of it landing in the hands of the Capuchins. She even refused when he wanted to exchange it with another piece of land with higher value. As God dislikes individuals who value their ownership rights and who are uncooperative towards self-professed morally-upright religious fanatics, she was struck with an incurable disease and dropped dead after six months.

Her daughter, the new owner of the property and barely 18 years old, happened to be as stubborn as her dead mother. She rented it out to tenants in order to earn premium on her property as other normal landowners would do, but the house is now haunted by a malicious ghost. Pots and pans were dancing in the air and the floor and cupboards were rattling. An invisible hand supposedly strangled a pet (possibly a cat). The angry ghost even appeared to the housewife who just moved in and drove her out.

Then two nuns moved in. On the first night, the ghost came down from the cellar and pulled up one of the sisters’ by her hair. The next day, the nuns were so shaken they lit as many candles as they could and prayed till the cows come home, hoping the ghost would leave them alone. But it did not. The second night, it tortured them again. Possibly by pulling their hair again. When the dawn broke, the two nuns fled away from the cursed house.

On 26 March 1592, exactly at 9 in the morning, the young landlady ran barefooted to Mr Bajus, begging him to buy the property from her. By noon, the land belonged to the Capuchins.

The Expansion of the new Monastery

It seems that once the Capuchins got their land, the haunting stopped.

They started breaking down the house and also the empty nearby houses that used to belong to plague victims. By 27 January 1595, the church was opened.

In 1597-98, there were 8-9 Capuchin friars. They soon increased to 12-13 and needed a bigger monastery and more land (which was a bit strange for an anti-capitalist religious order campaigning for poverty for all).

The fathers bought an adjoining piece of land in 1611 and their ever generous donor Bajus got them a neighbouring garden in 1613. Then on 14 July 1615, the President of the Chamber of Accounts of Brabant, bless him, gave them the land (which no one claimed, most likely another plague victim) that joined their monastery with the River Voer.

In 1629, the monastery housed 35 cells and 5 sick bays for the poor and ill. In 1725, there were 41 cells and all were fully occupied by 13 friars and 28 novices. The number of sick bays did not increase and travelling monks from outside of Leuven get priority to use the sick bays as hotel rooms.

To be fair, taking care of plague victims was a tradition of the Capuchin Order. There was said to be two “plague houses” in the monastery gardens at least before 1667.

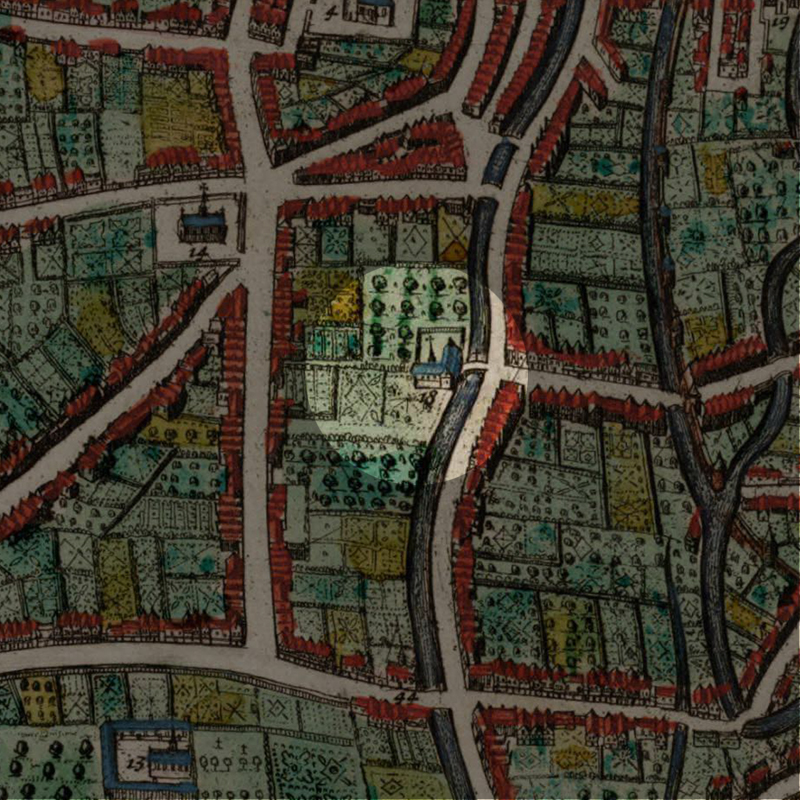

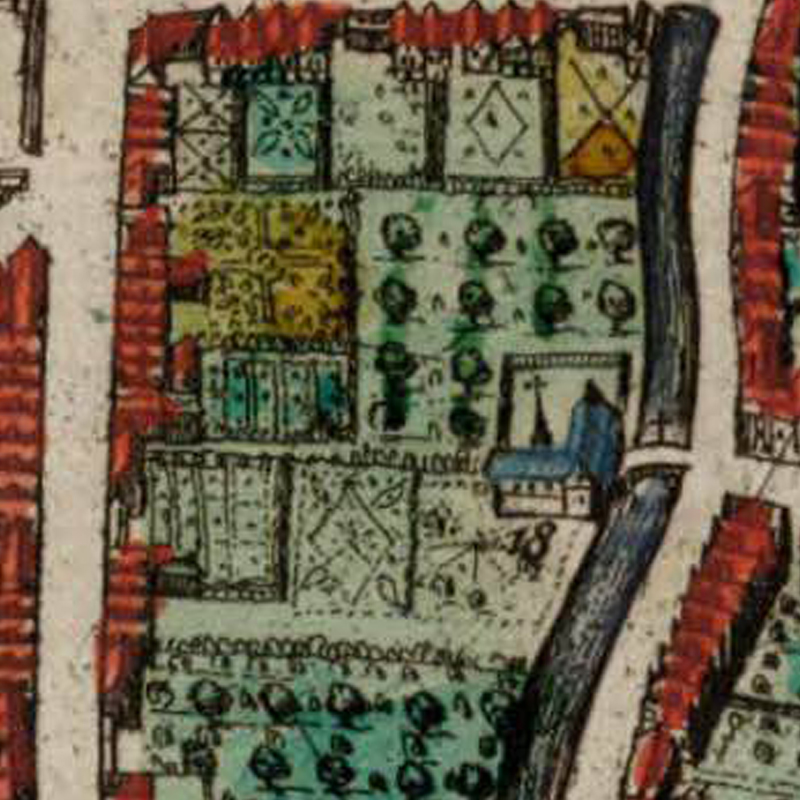

According to written accounts, the entrance to the Kapucijnenklooster by the river bank of the Voer, directly across the Minderbroedersstraat, to which it was connected by a bridge. You can see how this looks like on our cartographer’s map.

On 28 November 1796, the Capuchin Monastery, as with the other religious orders in Leuven, came to an abrupt end. According to the accounts of a certain J. B. Hous, a band of “hunters” chased the friars out of their monastery with “a saber in the hand”. By 16 March 1797, the furnitures of the monastery were taken out and sold. So were the buildings.

According to chronicler M. F. Pelckmans, the square shaped land of the Kapucijnenklooster from the River Voer to the Heilige Geeststraat was sold in April 1797 for 200,000 francs.

By 1819, the French were chased out and the Leuven city adminstration bought the land back from the private owners. But by that time, there was absolutely nothing left of the former Kapucijnenklooster.

In memory of the Capuchin friars, the city renamed the now-covered River Voer – after it was called “Rue de la Liberté” (Freedom Street) by the French thugs – as the current-day “Kapucijnenvoer”.

What's so special about this place?

The Voer: A River Runs Through

Not known to many. Leuven was formed around the meeting of two rivers: the River Dijle with its many arms and the River Voer.

The River Voer starts in Tervuren, flows through the picturesque villages in the valleys before flowing into Leuven. At the foot of the Keizersberg Hill, the river merges with the River Dijle.

When the second city walls (current day ring road around Leuven) were builtin 1357, two sluices were built to control the flow of the two rivers in 1365: The bigger “Grote Spuye” for the Dijle and the smaller “Kleyne Spuye” for the Voer. Today, the Grote Spuye is still there. The Kleine Spuye has disappeared but you can see traces of it along the Tervuursevest outside the ring, in between the two Voer Viaducts, and then it resurfacing just in front of the big apartment block at the start of the Kapucijnenvoer.

The Cuythoek: Home of Mathieu De Layens

As mentioned before, the Kapucijnenvoer is the road covering over the River Voer.

The name of the road stops at the triangular little square called “De Cuythoek” which existed already in 1252 as “Coithuc“. This used to house many breweries in the Middle Ages, and the name derived from a beer brewed here called ‘cuytbier‘, where ‘cuit‘ is French for ‘cooked’.

In the 15th century, the back of the Cuythoek was home to Leuven’s famous architect Mathieu De Layens. Died in 1483, De Layens designed Leuven’s City Hall (Stadhuis )and his last work was the Tafelrond.

The Cuythoek is now a popular bar in the neighbourhood. Sadly, there is no mention of Mathieu De Layens by the city administration.

A street with two names

Once the river passes the Brusselsestraat as it goes northwards, it becomes a pedestrian street and changes its name to Fonteinstraat (“fountain street”). The street on the left is called Tessenstraat. There is currently two small fountains and drains that run along this pedestrian street as a reminder of the river that runs underneath.

After the pedestrian street ends, the Fonteinstraat then continues all the way as a road to Keizersberg where the river resurfaces again behind a row of houses to flow into the Dijle at the Sluispark.

The Capuchin Fountain

The current neo-classical entrance to the Kruidtuin is exactly where the old entrance to the Kapucijnenklooster was located. By the gate, there was a fountain called “De Bollenborne” which by the 17th century came to be called the Capuchin Fountain (Kapucijnen-fontein). In 1621, the city treasurer Gaspar de Pape renamed it offically “Nieuwe Verloren Kost”. By the 19th century, the fountain was replaced by a water pump, for the benefit of all. Today, there is a fountain just inside the gate of the Botanical Garden to the right of the official entrance, in memory of the original one.

The Anatomical Theatre

Directly opposite the Kruidtuin entrance, you see a round 18th century building. This was the former anatomical theatre of the university from 1744-1797. Designed by Jacques-Antoine Hustin, the building was commissioned by Rector Hendrik Rega to urgently replace the current one, as the citizens protested against dead bodies being carried in and out of the Lakenhal on the Naamsestraat right in the centre of the city.

As mentioned, the entrance of the first Botanical Garden (which was liteally next door) served also as the entrance to the Anatomical Theatre in order to disguise its use.

By 1797, the French Revolutionaries forbade the dissections, and all anatomical preparations were moved to Brussels.

When Belgium and the Netherlands came together the second time as one country under King Willem I, he refounded the Leuven University in 1818 and encouraged the study of anatomy in 1835. As a result, the Vesliusinstituut was founded just behind the Sint-Pietersziekenhuis further down the same Minderbroederstraat, so that the dead could easily be carried over for dissection without the prying eyes of pesky inhabitants.

Current situation

One of Leuven’s Most Beautiful Spots

The idea to build a botanical garden came from Rector Hendrik Rega. Since 1738, Rega built a medical garden in a small piece of land between the River Dijle and the River Voer. But soon, this garden became too small for its use and the opportunity came when the state bought the land belonging to the former Capuchin Monastery just across the Voer. Today, the only remnant of this first garden is the neo-classical gate at Number 50 Minderbroedersstraat, with the word “Hortus Botanicus“, designed by L.B. Dewez in 1771.

The second Botanical Garden turned out to be a huge success. Designed by Charles Vander Straeten (1771-1834), the head architect of the Prince of Orange and laid out by Leuven’s garden architect Guillaume Rosseels (1769-1832) under the guidance of German botanist J.F. Adelman, this new garden contained an entrance building (on the site of the former entrance of the monastery) with a gardener’s cottage, an orangerie, as well as surrounding walls in strict classical style.

A tropical glasshouse was added in 1984, and in the same period, the former Apostoline Convent (Marollenklooster) was incorporated (Number 32 Kapucijnenvoer) to form the fruit garden and the Victorian sunken garden.

Today, the Kruidtuin is one of Leuven’s best-kept secrets.

It is one of the city’s most beautiful spots and offers a place of solace for some quiet reading and contemplation.

The garden is designated national protected landscape and the glasshouse national protected monument in 1976.

Sources:

https://search.arch.be/nl/zoeken-naar-archiefvormers/zoekresultaat?text=eac-BE-A0500_112401&view=eac&inLanguageCode=DUT&limitstart=0

P. Hildebrand, “De Kapucijnen te Leuven” in “Kapucijnen in de Nederlanden”, Antwerpen, 1945-1956, p.415-459

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/42252

http://leveninleuven.be/2014/07/08/een-stukje-geschiedenis-de-kruidtuin-van-leuven/ (photos)

http://www.leuven.be/vrije-tijd/toerisme/bezienswaardigheden/park-en-natuur/kruidtuin.jsp

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/42252

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/themas/15131

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/42179

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.