ABOUT

The Wolvenpoort (The Wolfs Gate) was located on the Schapenstraat, at the foot of the hill east of the Proefstraatpoort.

Origin

The First and Inner Defence Wall of Leuven: After 1190

In the Early Middle Ages, Leuven was defended by a primitive fence that stretched from the Aardappelmarkt (modern-day Vital Decosterstraat) to the Redingenstraat, while an arm of the River Dijle formed a natural border.

By the 13th century, when the city grew to be the permanent residence of the Count of Leuven and Brussels, the need for a stronger defense bulwark became urgent. Historians have traditionally dated the construction of Leuven’s first defense walls to be between 1156 and 1165, during the reign of Count Godfried III, due to the yearly tax he imposed on citizens for defense. However, the military features of Leuven’s wall such as anchor towers, arrowslits etc cannot date before the 1200s, making this estimate too early. It is now generally accepted that Leuven’s first city wall was built by Henry I (Henrik), the first Duke of Brabant (1190-1235). He also abolished his father’s defense tax in 1233.

Constructed with layers of sandstone from nearby Diegem and Zaventem and ironstone, the first defense wall was roughly 2,740 metres long with 31 watch towers, 11 city gates and 2 water gates.

The wall measures 1.70m thick and rests on a series of underground arches. On the field side, the wall rises to about 5m tall. On the inside, a continuous series of arches supported a three-foot-wide walkway. The wall had arrowslits that were reduced on the outside to a narrow opening of 90cm high and 5cm wide.

However, as the city grew rapidly in size, a second (outer) more impressive defence wall was built in 1357, rendering the inner wall somewhat redundant. But the inner wall and gates were not immediately torn down. Most of it only disappeared in the 18th and 19th centuries. Even so, we see more of Leuven’s inner city wall today than the more recent outer city wall. Very well-preserved remnants of the 12th-13th century wall can still be seen in the City Park, as well as in the Refugehof, the Handbooghof, in the Redingenstraat behind the Irish College, and on the Hertogensite. The outer city wall and gates were torn down completely in the 19th and 20th centuries to become today’s ring road around the city.

Below is the list of the gates of Leuven’s first city wall starting from the north going eastwards:

- Steenpoort

- Heilige-Geestpoort

- Sint-Michielspoort

- Proefstraatpoort

- Wolvenpoort

- Redingenpoort

- Broekstraatpoort/Liemingepoort

- Justus Lipsiustoren-Janseniustoren*

- Minderbroederspoort

- Biestpoort

- Minnepoort

- Borchtpoort

- Sint-Geertruisluis*

*water gates.

How did the Wolvenpoort look like?

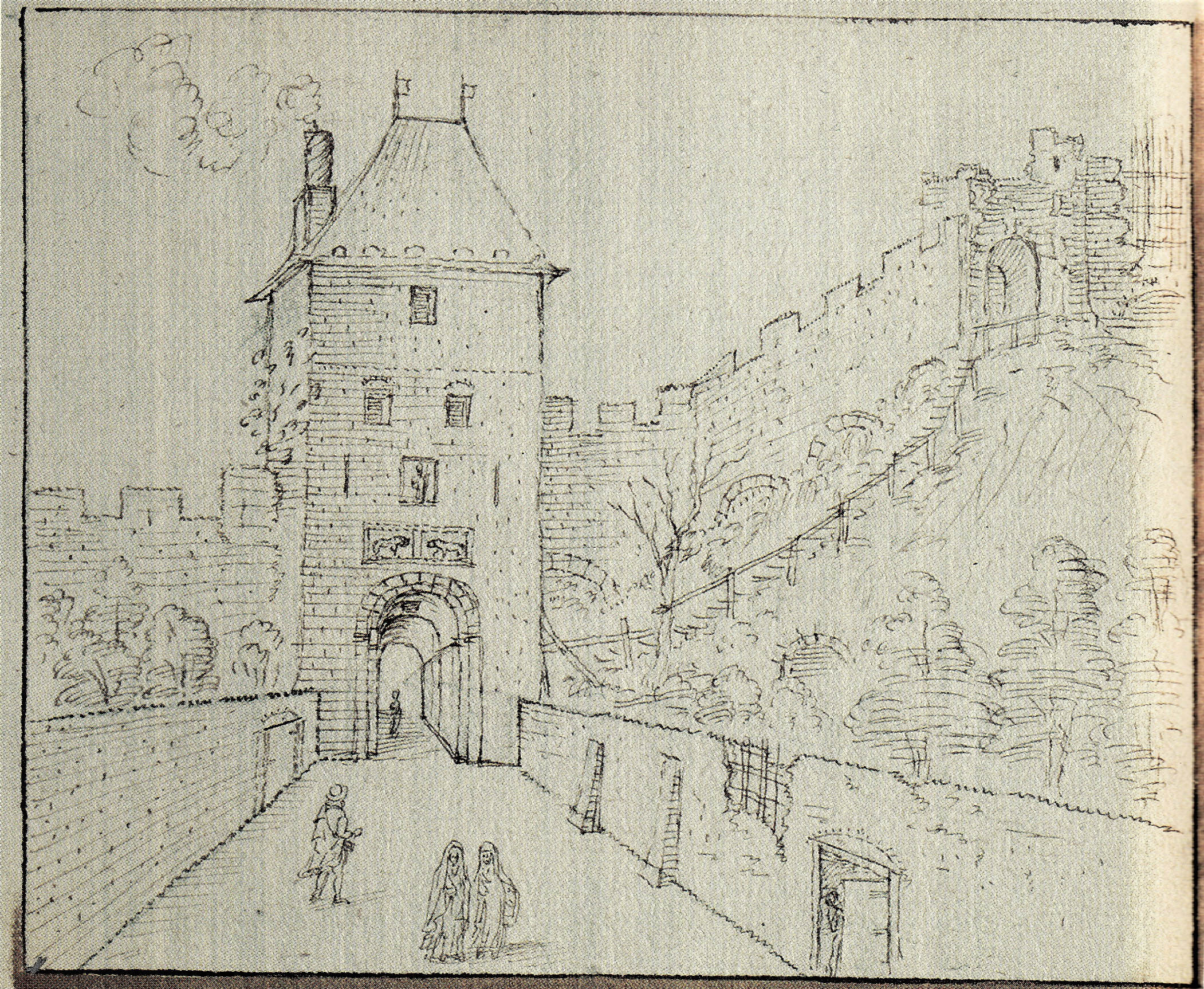

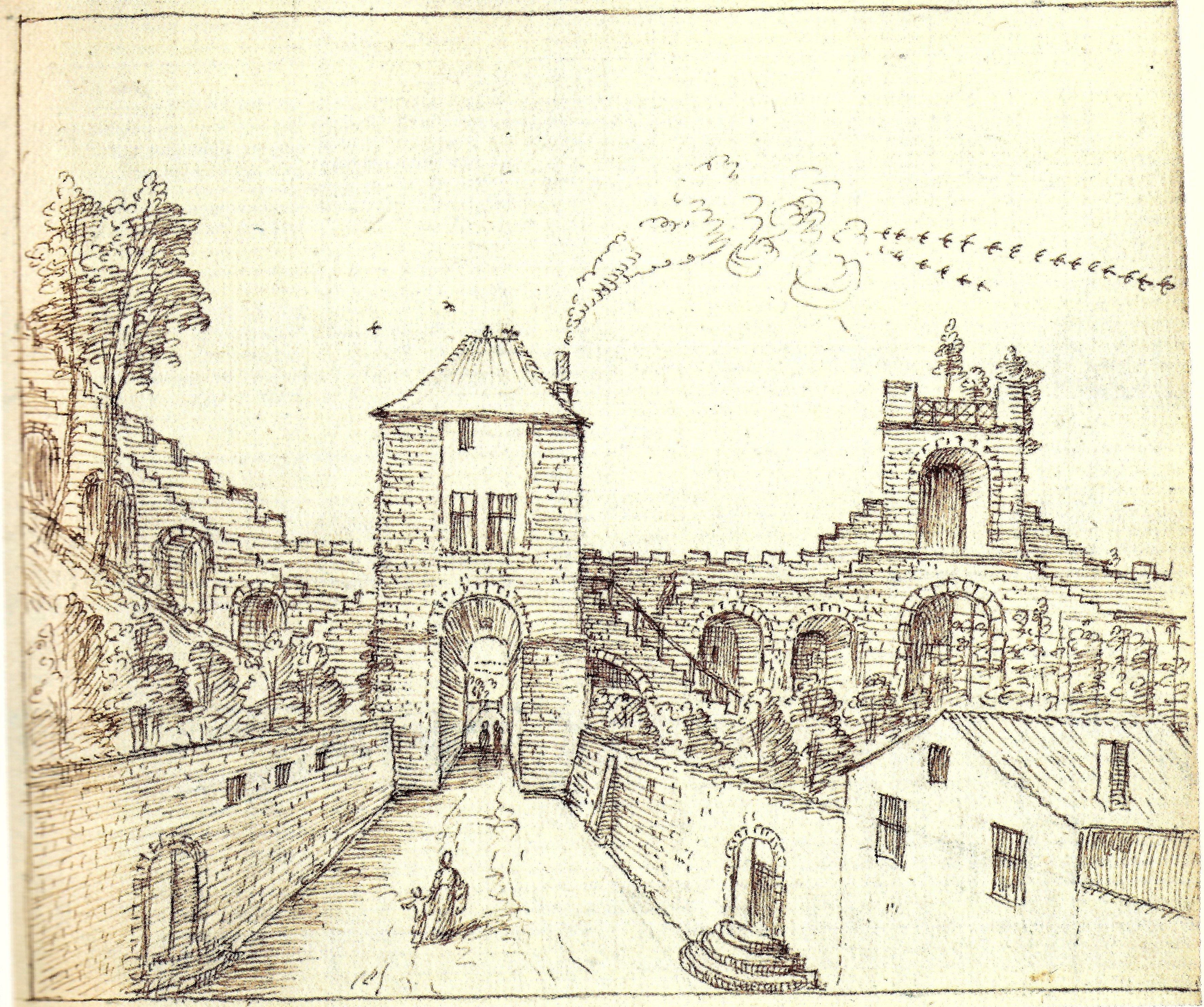

The Wolvenpoort was named after the two wolf bas-reliefs that adorned the gateway on the outside. Like the Proefstraatpoort, the Wolvenpoort was rumoured to be built in the 9th century by the Vikings, which was certainly untrue. Unlike the Proefstraatpoort, there was no consensus among historians that the Wolvenpoort dated before the inner city wall. But the wolf motifs and another decoration certainly made it unusual to be part of the first city fortification.

The Cult of the Wolves

The Wolvenpoort would have looked like the other of Leuven’s inner city gates, flanked by two semi-circular towers rising two storeys high. In folks’ tongue, it was called the Begijnenpoort because it led directly to the Groot Begijnhof (Great Beguinage) located outside the city. 19th century historian Edward van Even explained that the wolf was very much sacred to the Vikings, who brought them on raids in the Low Countries. While it is certainly not possible that the gate was built by the Vikings in the 9th century, the Wolvenpoort did look very different in colour, as it was built entirely in the same grey stone as the wolf bas-reliefs.

Also, the wolves’ link to the Vikings cannot be fully dismissed. As recounted in my post about the Groot Begijnhof, from an etymological point of view, the site could very well be the spot of the Battle of Leuven (Slag bij Leuven), on 1 September 891, where the Vikings were defeated and of the first court of Leuven. Could the wolves be a symbol of the victory over the Vikings?

What's so special about this place?

The Big Penis Gate

The other mystery that has surrounded the Wolvenpoort for centuries was the statue that used to stand between and above the two wolves.

While some saw the figure as a male warrior holding what looked like a large spear, others said he was in fact holding his own gigantic penis. Willem Boonen, Leuven’s city archivist who wrote in 1593-1594 said the figure was indeed a naked Priapus holding his massive cock, based on city councilors’ letters from 1149:

“Sommige oude scriften houden in dat sommige Poorten van de stadt Loven by hen (de Noortmannen) gemaect syn geweest, ende onder andere de Wolffspoorte, op de welcke, van grauwen steen, gehouden staet een beelt van eenen Affgodt, al naect, met een colve oft stocke inde handt, ende wordt dese Poorte, in oude schepene brieven van Loven vande jaren 1149 ende ooc van de jaere 1200, ende voordere, in den latyne genoemt PORTA PRIAPI, waeruyt schynt dat sy eenen affgodt, genoemt PRIAPUS, aldaer aenbeden ende in reverentie gehouden hebben.”

This account was confirmed by 16th century historian Jan Baptist Gramaye (1579-1635) who found in Liège an index of Leuven’s chapels, including “a Chapel of the Holy Virgin inside the Gate of Priapus“. Now take a moment of silence to absorb all of that.

Others were more coy about the Priapus connection. Petrus Divaeus (Peeter van Dieve) historian and humanist (1535-1581) said he could not make out the character due to the weathered state of the statue. Justus Lipsius (1547-1606) said while he had not seen the figure, some of his contemporaries thought the figure could Priapus while others thought it could actually be Mars the Roman God of War. Unfortunately, the Mars theory lasted right into the 18th century but not that of Priapus.

When we compare this to the Semini bas-relief on Het Steen the 13th century city gate in Antwerp, which is still visible today and also a phallic symbol, It could very well be that the statue on the Wolvenpoort was indeed Priapus. This theory is plausible, especially based on the records of the Wolvenpoort being originally called the Priapus Gate.

Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing

The street that leads from today’s Pater Damiaanplein right up to the ring road of Leuven is called Schapenstraat (Sheep Street). Back in the Middle Ages, this was one single street together with the Parijsstraat that connected the Brusselsestraat all the way to the Wolvenpoort. It was called the “Legestrate” or “Ledigestrate” (Empty Street), after the ‘Ledige Plaats’ (Empty Square) that is the Pater Damiaanplein.

So why was it called the Empty Square and why is it called the Sheep Street today?

As explained in the post about the Pater Damiaanplein, the square where the Veemarkt (Cattle Market) used to be was already known in the 13th century as the ‘Lagere Plaats‘ (Lower Square). This is because the city was divided into upper (where the Naamsestraat is) and lower towns (from Parijsstraat all the way to the end of Schapenstraat), and the Lagere Plaats was the place of gathering for people in the lower town.

Before it became a square, there used to be a wooden grain hall standing here housing Leuven’s first Korenhuis (Grain House).

In 1293, the Duke of Brabant Jan I gave the square to the city, on the condition that it would never be built on. This condition still stands today.

The Korenhuis has since been moved to the Zeelstraat by the Grote Markt.

Because of this condition, the square became known as the ‘Ledige Plaats’ (Empty Square), and the street leading through became the ‘Ledigstraat’ (Empty Street).

With the square being empty, it soon became the spot of the Cattle Market (Veemarkt), focusing very much on the sale of pigs. The street from the square to the Wolvenpoort focussed on the sale of sheep, hence this part of the road became known as the Schapenstraat (Sheep Street). Once the pig market moved to the new Sint-Jacobsplein outside the Sint-Jacobskerk, the market focused instead on selling chicken and pottery.

Victims of the Wolvenpoort

In 1363, the city conducted a huge restoration of the Wolvenpoort, after the roof collapsed and all its windows and doors had to be completely replaced. The work was carried out by Henric Samme (master mason of Leuven) and Henric van Nijmegen. In the course of the 15th century, other works were done. But not before long, the Wolvenpoort started to decay, together with the inner city walls connected to it.

In his “Louvain monumental ou Description historique et artistique de tous les édifices civils et religieux de la dite ville“, Edward van Even wrote about the demolition of the city wall by the Van Dalecollege that led to the Wolvepoort.

On 14 May 1630, the judge permitted the management of the Van Dalecollege to demolish the old city wall at a length of 50 feet along the property’s southern borders, on the condition that they replaced it with a new wall at their own cost. A few years later, on 19 May 1642, he also granted them the permission to use the existing slots of the city wall in their garden to reconstruct the parts that have already crumbled down.

Nothing was recorded as to whether work to replace the walls or to repair the crumbling walls actually took place, but the inevitable happened. The part of the wall linked to the Wolvenpoort fell on 31 September 1683 at around 8pm. The house attached to the gate was crushed, killing five persons including a mother with her suckling baby.

Between the permission and the accident, 53 years went by. The tragedy would not have happened had the walls been repaired early enough. Some things never change…

If you walk along the southern wall in the forested area of the park, you can still see the foundations of the old city wall.

In memory of the Wolvenpoort

On 29 January 1779, the Wolvenpoort that has become a pile of dangerous ruins was put on auction. Somewhere in February, it had entirely disappeared. The porter’s house and its garden were sold to a Jean-Baptiste Meynaerts, where Number 34 Schapenstraat now stands. Antoine-Dominique Mosselman, President of the Van Dalecollege, bought the two wolf bas-reliefs, and put them up in the college’s garden wall. They are still visible today. Van de Velde, the chief librarian of the old University of Leuven, wrote the following Latin inscription carved in stone and placed between the two wolves.

LUPORUM . PAR . QUOD . PORTAE

LUPINAE . HUIC . OLIM . LOCO

CONTIGUAE . ANTEQUAM

SENATUS . JUSSU . ABHINC

BIENNIO . DESTRUERETUR

IMMINEBAT . IN . HUNC . PARIETEM

OB . MEMORIAM . TRANSLATUM

FUIT . AN . DOM . MDCCLXXXI

COLLEGIUM . DALENSE.

The words mean “The two wolves that dominated the Wolves Gate that formerly stood close to this spot were placed as historic monument in this wall, in the year of our Lord 1781, two years after the Senate of the Commune decreed its demolition.“

Current situation

Thanks to the Antoine-Dominique Mosselman, the relics of the Wolvenpoort survived the destruction of the edifice and are still visible today to all of us. It is a shame though that no one now would ever know if the naked male figure truly was Priapus, but just like the wolf sculptures themselves, this mystery adds a whole lot of allure to the history and the story of the Wolvenpoort.

Sources:

“Louvain dans le passé et dans le présent“, Edward van Even, 1895

“De Leuvense Prentenatlas: Zeventiende-eeuwse tekeningen uit de Koninklijke Bibliotheek te Brussel“, Evert Cockx, Gilbert Huybens, 2003

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ringmuren_van_Leuven

https://www.erfgoedcelleuven.be/nl/stadsomwalling

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/125406

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/erfgoedobjecten/42456

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/themas/8254

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolvenpoort

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.