ABOUT

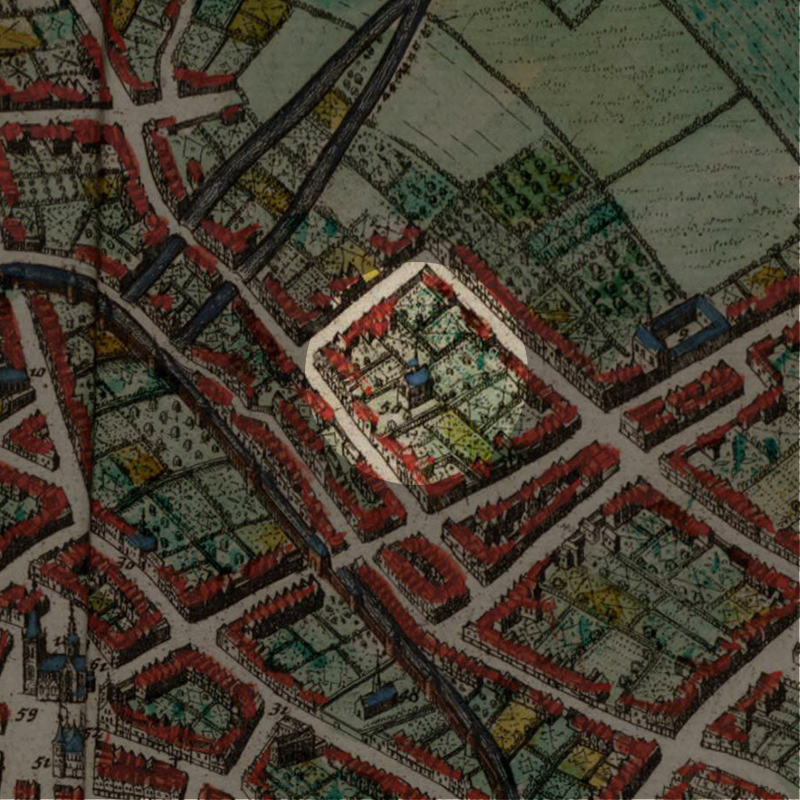

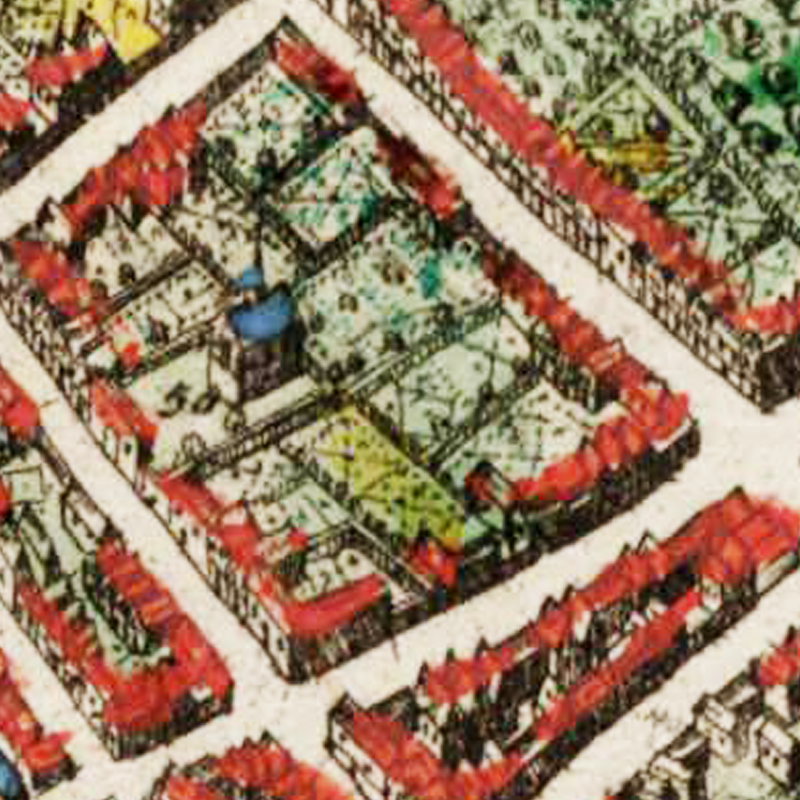

The cartographer made a mistake. On the spot marked Number 50, was not a school for the poor, but the Priory of St Martin’s Valley (Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal) which existed from 1433-1784. Today, it is the iconic public housing blocks known by the same name ‘Sint-Maartensdal’, between the Sint-Maartenstraat and the J.P. Minckelersstraat.

Origin

The House of Professor Henri Wellens

In 1408, Henri Wellens, Chapter of the Sint-Pieterskerk purchased for himself and his mother, Christine Van Den Winkele, a house with a straw roof surrounded by a huge garden along the Grymstraat/Grimdestraet (present-day Sint-Maartensstraat). At that time, this was still an uninhabited part of the city.

As an alumnus of the University of Cologne, having graduated with a baccalaureate in theology and a master in the arts, Wellens was in fact one of the first professors in the Faculty of the Arts at the new University of Leuven in 1426.

Soon, Wellens started to turn his home into a pedagogy – not unusual in those times – so that students could not only lodge there, but also attend extra lessons in Latin.

The Lindisfarne of Leuven

Upon his death, as recorded in his testimony of 22 February 1433, Professor Wellens left his home to the Brethren of the Common Life (Broeders van het Gemene Leven), a religious movement from Deventer. The Brethren sent two friars, Egide Walram and Werner de Zutphen, to Leuven with the aim of building a new priory in keeping with the idea of providing education as did the pedagogy set up by Wellens.

Known by the lengthy name of ‘The House of Clerical Congregation on the Grymstreet‘ (Domus seu Congregatio Clericorum, in platea dicta de Grymstrate), the new priory would focus on youth education in calligraphy and manuscript writing.

A century after its founding, the priory grew to the size of 50 disciples.

On 16 March 1435, the Chapter of Sint-Pieterskerk gave his consent for the construction of a small chapel in the new priory. It was consecrated on the day of St Martin and under the invocation of St Gregory, patron of the clerks, thus gave the priory its Latin name of ‘Domus Presbyterorum et Vlericorim SS Martini et Gregorii. Later, when the priory grew in size, its formal name became: Monasterium vallis Sancti Martini in Lovanio – Monastery of the Valley of St Martin in Leuven.

During the two centuries that followed, the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal’s focus on caligraphy and manuscript-copying turned it into the Lindisfarne of Leuven.

The friars copied religious and academic works by hand, and in 1525, when the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal was incorporated into the University of Leuven, its library became the crown jewel of the university. The library possessed more than 550 valuable manuscripts, most of which were transcribed by the Priory’s monks themselves.

A visit by a Friar Sanderus in 1662 recorded that in as late as the mid-17th century, the friars of the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal were still writing on parchment, despite the fact that printing was already popular.

The Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal did try its hand at printing, producing a few tomes themselves. But since the costs incurred were too high, they decided to focus on transcribing works of ecclesiastical nature.

Nicolaas van Winghe and the Leuven Bible

Among its well-known friars, was Nicolaas van Winghe, author of the biblical translation called the Leuven Bible (Leuvense Bijbelvertaling) published in 1548.

Nicolaas van Winghe belonged to one of the Leuven noble patrician families. After completing his study at the Leuven University, van Winghe entered the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal first as a copyist and by 1532, he became the Chief Librarian and later Sub-Prior.

When the publisher Bartholomeus van Grave received the right in 1546 to print authorised version of the bible, he sought the help of Nicolaas van Winghe for the Dutch version of the new Vulgate. By 1547, the Leuven Bible was completed and was published the next year.

The Spanish Fury

Emboldened by his victory at Den Briel in 1572, William of Orange started marching south. Leuven’s city and university drew up a new tax on beer, wine and real estate called “gemeyne middelen” to build up the city’s defense. But on 3 September 1572, Orange’s forces marched into the city. The people of Leuven realised that it was impossible to defend the city, and they paid the ransom of 16,000 florins to avoid being plundered.

But since the war has arrived at the doorstep of Leuven, many students fled the city, so had the friars of the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal. After 1578, there was almost no students left in Leuven and the Priory was completely emptied.

To fight back the rebels led by Orange, Catholic troops from the rest of the Holy Roman Empire arrived in Leuven – from modern-day Spain, Italy and Germany, including mercenaries from all over.

During the Eighty Years’ War of the Dutch Revolt, the citizens of Leuven suffered from the plundering and bullying of these troops. Merchants were consistently robbed. Inhabitants went as far as Namur to sell their furniture to pay ransom to these Catholic soldiers.

Now called the Spanish Fury, the plundering, robbing and killing by Habsburg troops in the southern Low Countries ended in the greatest massacre in Belgian history with the Sack of Antwerp (1572–1579).

By the end of the Spanish Fury, the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal never recovered.

A New Chapter for the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal

With an empty priory, the Archduke Albrecht and Archduchess Isabella, Rulers of Spanish Habsburg Netherlands, allowed the friars from the destroyed Monastery of Maria’s Throne in Grobbendonk to take over the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal. They renamed it ‘Priory of Maria’s Throne in St-Martin’ (Maria’s Troon in Sint-Maarten).

While the new friars tried to continue the manuscript-writing tradition of the old Priory, the intellectual capacity of the previously-renown Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal was lost forever.

With the edict of Habsburg Emperor Joseph II, all religious abbeys that were ‘useless’ in his eyes were shut down in 1784. This included the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal. All of its properties were sold and the Austrian Habsburg troops turned the priory into a military base from 1784 to 1790.

The Military Base of Sint-Maartensdal

The friars did return to the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal after the edict was lifted in 1790, only to be kicked out again when the French invaded in 1796. Its remaining eleven friars left that year, including the last and the thirtieth Abbot of the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal, Jacques-Guillaume Bosmans, who died in 1797.

After the French invaders were defeated, the Belgian army took over the buildings and turned it once again into a military base for both infantry and cavalry. The refectory of the Priory was converted into the sleeping quarters, and was said to have ceilings covered in religious bas-reliefs (see photos). This military base, right in the centre of Leuven, became known as the Sint-Maartenskazerne.

The Sint-Maartensdal Council Housing Project

After Leuven was devastated by the two World Wars in the first half of the 20th century, the city administration received the land back from the military base of Sint-Maartensdal to build housing for the increasing population. The architects were given the challenge in 1956 to build on this site, housing for 687 households. Considering that the terrain of more than 4 hectares in the centre of the city was precious real estate, the architects decided to go for modern high-rise flats that would dominate the skyline of Leuven.

This social housing project’s construction lasted more than a decade, from 1960-1971. Designed by architect Renaat Braem, the new Sint-Maartensdal gave Leuven several iconic tower blocks, the tallest of which is now a symbol of Leuven – with a spire measuring 40m tall on top of the building both measuring 115m.

What's so special about this place?

The Jeskesboom and the Coolest Spot in Leuven

In the 15th century, this part of the city of Leuven where the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal was situated was sparsely populated. There was nothing apart from large fields of wild flowers and small vegetable plots here and there. The area was called ‘Coelheem’, ‘Coelhem’ or ‘Coolhem’ meaning ‘cool place’. At the entrance to this ‘cool place’, there was a tree with a hollow space where a crucifix was placed, and locals called this ‘Jesuskens-Boom‘ – the Jesus Tree. The spot is marked today by the bar of the same name ‘Jeeskesboom‘.

After the priory was founded, the name ‘Coelhem‘ disappeared, replaced by the name ‘Sint-Martensbeemden’, to designate the wooded area between the Diestsestraat and the tree, all the way up to the walls of the priory. There used to be a small stream running behind the Jeskesboom called the ‘Leibeek’, which separated ‘Coelhem’ from the Diestsestraat. This has perhaps dried up or is now running underground.

Today, the J.P. Minckelersstraat is the official name of the street that runs from Diestsestraat to along the right of the Sint-Maartensdal.

In the locals’ tongue, it is called “‘t Koulejan“, a corruption of its 15th-century name ‘Coelhem’.

The Grymstraat/Grimdestraet on the left of the Sint-Maartensdal is now known as the Sint-Maartenstraat, named after the former Priory.

Current situation

There is absolutely no trace anymore of the Priorij van Sint-Maartensdal – its once great library and the magnificent collection of precious manuscripts. Some of them are now housed in the Royal Library in Brussels. For the Belgian military base, there are an artillery and two small monuments, in honour of the sacrifices made during the two World Wars by the former ‘Regiment van de Rijdende Artillerie‘ (regiment of the riding artillery) that used to station there.

Sources:

https://inventaris.onroerenderfgoed.be/themas/15106

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Priorij_van_Sint-Maartensdal

https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leuvense_Bijbel

https://search.arch.be/ead/BE-A0518_116910_115645_DUT

https://www.bouwkroniek.be/article/dijledal-renoveert-iconische-torenspits-sint-maartensdal.31729

https://belgiummilitary.wordpress.com/vastgoed-geklasseerd-per-gemeente/leuven-louvain/leuven-sint-maarten/

Louvain monumental ou Description historique et artistique de tous les édifices civils et religieux de la dite ville, by Edward van Even, 1860 (image)

HOW IT LOOKS LIKE TODAY

Click on the zoom icon to view the full size.